- Home

- Elmore Leonard

Unknown Man #89 jr-3 Page 7

Unknown Man #89 jr-3 Read online

Page 7

He had to put the envelope in the left-side pocket. His hand came out and finished unzipping the raincoat, pulling the skirt aside. The heavy stubby front end of the twelve-gauge appeared.

“And thank you, honey,” Virgil said to the boy sitting there bare-chested with his chains and his hairnet and his mouth open. Virgil gave Lonnie a double-O twelve-gauge charge from ten feet away, pumped the gun hard with his left hand and hit him again, whatever part of him it was going out of the chair ass over hair dryer, making a terrible noise and shattering a full-length mirror, wiping it from the wall, as the beauty-parlor man began to scream, backing away.

Virgil stared at him, frowning at the painful sound, until he lowered the blunt end of the shotgun and zipped the raincoat over it. The beauty-parlor man stopped screaming. Virgil continued to frown, though now it was more an expression of concern.

He said, “Man, get hold of yourself.” And walked out.

8

THIS END OF the hallway was dark. On the wall, near the door, was a light fixture shaped like dripping candlesticks, but there were no bulbs in it. Ryan had to strike a match to read the room number. Two-oh-four.

He listened a moment before trying the door. The knob was loose, it jiggled, but wouldn’t turn either way. He knocked lightly on the door panel and waited.

“Lee?… You in there?”

He had driven past the Good Times Bar and the place was empty. If she wasn’t here…

He knocked again, giving it a little more but still holding back, and waited again. There was no sound. Silence. Then a creaking sound. But not from inside the apartment.

The figure approached from the far end of the hall where a dull orange glow showed the stairwell: a dark figure wearing a hat, coming into the darkness toward him.

“You locked out?” Virgil said.

A black guy who was bigger than he was-three o’clock in the morning in a dark hallway. Ryan did not have to decide anything. If the guy was armed he could have anything he wanted. The nice tone didn’t mean a thing.

“There’s supposed to be somebody in there,” Ryan said. “She’s expecting me, but I think she might’ve passed out.”

“Let me see,” Virgil said.

Ryan stepped out of the way. Virgil moved in. He tried the knob, then took a handful of keys on a ring from his jacket pocket. Ryan thought at first he had a passkey. No, he was feeling through the keys, trying different ones in the lock.

“Are you the manager?”

“I seen you, I wondered if you locked out.” Like he happened to be standing in the hall, three o’clock in the morning.

“You live here?” Ryan asked him.

Virgil didn’t answer. He said, “Think I got it. Yeah…” He pushed the door open gently, took a moment to look in, and stepped out of the way.

“Your friend laying on the bed.”

A dim light from somewhere showed the girl’s legs, still in the Levi’s, at one end of the narrow daybed. Ryan tried to move quietly across the linoleum floor. He could hear her breathing now, lying on her back in a twisted, uncomfortable-looking position, her hips turned as though she had tried to roll over and had given up. The place smelled musty. The only light, a bare fifty-watt bulb, hung from the ceiling in the kitchenette part of the room. The faucet was dripping in the sink. There were dirty dishes, a milk carton, an open loaf of bread on the counter. A jar of peanut butter with the top off. Three half-gallon wine bottles, empty, on the floor. The only window in the room, next to the bed, showed a bare, dark-wood frame, no curtains. A shade with brown stains was pulled below the sill. He could see her in here during the day, on a good day, the room dim, silent, the shade drawn against the sunlight and whatever was outside that frightened her. Alone with her wine bottle, feeling secure as long as there was wine in it, sitting in the rocking chair smoking cigarettes and forgetting them and burning stains in the wooden table.

She could use three weeks at Brighton Hospital. If she had the money, or Blue Cross. She probably didn’t have either one. It would cost about nine hundred. He had almost three thousand in the bank drawing 5 1/2 percent. How much did he want to help her?

Ryan went into the bathroom, felt for the light switch, and turned it on. They all looked alike. The rust stain in the washbasin. The dirty towel on the floor, from some hotel. The hissing toilet tank. A comb with matted strands of hair. One toothbrush. One twisted tube of toothpaste. He looked in the medicine cabinet. No prescriptions, no tranquilizers. Good. An almost empty bottle of Excedrin. He’d check the refrigerator before he left.

He had forgotten about the black guy and didn’t look for him in the room or by the open door. But as he knelt down next to the daybed, looking at the girl, he was aware of the rocking chair creaking with a faint, steady sound.

The black guy was sitting there watching him, the hat slanting down over one eye.

He turned to the girl again and brushed the hair away from her cheek. Her eyes were open and she was looking at him.

“You all right?”

“Fine.” Her eyes closed and opened again. She was a long way from fine, whatever that meant to her.

“I want to ask you a couple of questions before you go to sleep,” Ryan said. “You have any Valium? Anything like that?”

“I have some… Librium, I think.”

“Where? It’s not in the bathroom.”

“I don’t know.” Her voice was drowsy; she barely moved her mouth.

“Come on, Lee? Where do you keep it?”

“I don’t know. Someplace.”

“Don’t take any,” Ryan said. “You hear me? You’ll probably wake up, you won’t be able to sleep, but don’t take any pills, any kind, except the Excedrin’s all right. Lee?” He touched her shoulder and waited for her eyes to open. “You have any family here? How about your mother and dad, where’re they?”

“No, I don’t have-they don’t live around here. They’re home.”

“Where’s home, Lee?”

“Christ, you tell me. Home… shit, I don’t know.”

“How about friends?”

“What?”

“You know some people, don’t you? You have friends?”

“Fuck no, I don’t have any fucking friends. My friends disappeared.” She seemed awake now.

“You know people who live here, don’t you? In Detroit, around here somewhere?”

But she wasn’t awake. She was here and she was spinning around somewhere in her mind. Ryan remembered it, like falling backward and looking up at nothing, feeling a dizziness. He could hear the faint sound of the rocking chair creaking.

“Lee, try to think of somebody. People you used to know.”

“I don’t know any-no, hey, I know Art.”

“Who’s Art?”

“He’s a prick. No, he’s all right, he can’t help it.”

“Who’s Art, Lee?”

“The innkeeper. Don’t you know Art? Arty? Don’t call him that, though. He’ll fuck up your drink.”

“How about Bobby Lear?” Ryan said. “You know him, don’t you?”

There was a silence. The creaking sound of the rocker stopped, then started again, slowly.

“You said he called you. Lee, what’d he call you for? Tell me.”

She laughed then. “Man, that’s great. I said now you’re asking me. Man, you got a lot of fucking nerve.”

“What’d he want you to do?”

“He wanted me to help him. Jesus. I said Jesus, do you know where I am? Where you left me? I’m down in the bottom of a hole, that’s where”-her voice rose-“and I can’t see out!”

Ryan stroked her hair. Her forehead was cold, clammy. “You’re going to be all right,” he said. “Where is he, Lee? Where’d he call from?”

The creaking sound stopped again.

“I said what’s it like, man-all that man shit-I’m tired, you know, I’m tired of all that cool shit.”

“What’d you say to him?”

“I said what’s it l

ike, have it fucking turned around for a change?” She started to push up. “I think I’m going to be sick.”

“Here.” Ryan held her. Her head drooped, nodding, staring at the floor. He felt her pull away and let her sink back to the bed.

“Save it till morning,” she said. “No, what I need-you don’t happen to have a chill bottle of Pully, Poo-yee, shit, or even a warm bottle nigger strawberry pop wine. God, I don’t care. Something.”

Ryan waited. She let her breath out slowly, her head settling against the pillow.

“Where is he, Lee?”

“He’s at a place, the Mont… something. It’s down, you know, it’s down there by-the Montcalm. That’s the name of it.”

“A hotel?”

“Yeah, for whores and people like-I can’t, I don’t want to see him, Jesus, please.”

“You want to take your clothes off? Get under the covers?”

“Leave me alone.”

“Lee, I’ll be back in the morning. Don’t leave here, okay? And don’t have anything to drink. Promise me. If you feel the urge like you got to have something, call me. Anytime you wake up and feel it, call, okay? You got my number.” What else? He knelt there looking at her, trying to think. He’d stop by a drugstore in the morning and get some B-12 tablets, load her up with it, stay close, and help her through the bad time. Check the refrigerator. Check her purse for the Librium. He felt like a cigarette. What else? Ryan was aware of the silence then. He looked around at the empty rocking chair.

Virgil was at the end of the hall, his hat shadowed on the wall in the raw orange light over the stairway.

“Wait a second.”

Ryan got to him as he started down the stairs.

“You know that girl in there?”

Virgil looked up at him past the stair railing. “Do I know her?”

“Do you know who she is?”

Virgil seemed puzzled. “Don’t you?”

“Lee somebody. That’s all.”

“Say you don’t know who she is?”

“I was talking to her this afternoon, the first time,” Ryan said. “We got on drinking, I saw she had a problem.”

“Yeah, she got a problem all right.” Virgil squinted at Ryan then, suspicious. “You honest to shit don’t know who she is?”

Ryan tightened up a little. “If I knew, for Christ’s sake, I wouldn’t be asking you.”

“That’s Bobby Lear’s wife,” Virgil said.

Ryan stared at him. “But her name-that’s not his wife’s name. Lee?”

“I don’t know about her name,” Virgil said, “but that’s Bobby’s wife.” In the orange light he looked up at Ryan with an amused expression, almost a grin. “Shit, you don’t know anything, do you?”

Virgil started down the stairs.

“Wait a minute,” Ryan said. “Do you know him? I want to talk to him.”

“I do too,” Virgil said, his hat disappearing into shadow. The sound of the man’s steps, receding, came back to Ryan from the stairwell. The guy looked familiar. Like seeing somebody who played for the Lions in regular clothes. A black athlete, the outfit. The hat.

That’s what he had seen, the hat sitting on a bar. A colored guy with a cowboy hat. Not a cowboy hat, but like one. The guy sitting there had been wearing a maroon outfit, maybe like a leisure suit. He thought of Jay Walt. No, the maroon outfit had looked good on the black guy. Light-colored shirt with the collar out. And a tight strand of beads showing. The guy sitting near the end of the bar this afternoon when he left the place.

She had called from there an hour ago.

The guy could’ve still been sitting there. If it was the same guy. No, but he could’ve come back and been there when she phoned. And heard what she said. And then waited for him to come.

Why?

Because he’s the one who’s looking for Bobby Lear. Hanging around the man’s wife, waiting. Sitting in the rocker while he talked to her and hearing her say it. The Montcalm.

Shit, handing it to him.

Ryan went back into the apartment and found the Librium, two capsules, in the girl’s purse and put them in his pocket. He’d give them back to her tomorrow, if she wasn’t drinking. And bring some milk and a can of juice and a couple of eggs, which she’d gag on and refuse to eat. He looked through the room again to make sure there wasn’t another jug of wine hidden somewhere. Then looked at her, asleep, at peace for a little while. Mrs. Denise Leann Leary…

Leann. Lee. It had never occurred to him to look at the wife’s name and fool with it and see what else she might be called. He wondered if she had always been called Lee. When she was a little girl. Before she knew what wine tasted like. She had probably never looked this bad in her life. Her face puffy, blemished, her hair a mess. He didn’t remember the color of her eyes. Dark eyebrows, a nice nose and mouth. She could clean up and be a winner, if she wanted to. And he could stand here looking at her all night, what was left of it, and it wouldn’t do either of them any good.

Driving home, he planned his day.

Get up at eight, stop by a drugstore for some B-12 and be back at the girl’s place a little after nine. Try to get her squared away, in the right frame of mind and something in her stomach. Or if she was in too much pain, with her nerves screaming at her, see about getting her into a hospital. Then stop by the Montcalm Hotel and ask for a Robert Leary, Jr. No, Leary would be using another name. All right, he’d start knocking on doors, and if a man in his mid-thirties appeared, if he opened the door, he’d say how you doing? If you’re Robert Leary, Jr., we’ve got a whole lot of money for you, buddy. See if the real Robert Leary, Jr., could resist something like that. He’d have to make sure Leary was there. It wouldn’t do Mr. Perez any good to have just the address.

He was getting close now, but God, it was a lot of work. He was tired of thinking. He was tired of driving, being in the car. Tired of waiting around. But more tired of thinking than anything else.

It was after four by the time Ryan got to bed.

When the phone rang at ten to seven he opened his eyes and immediately thought of the girl, Lee, crying for a drink.

But it was Dick Speed’s voice with a pleasant good morning and how would he like to come down to the morgue and meet somebody.

9

IT WAS NEARLY EIGHT by the time Ryan got downtown.

The Wayne County Morgue-the exterior of the building as well as the lobby with its long polished-wood counter-reminded him of a bank. A uniformed police officer was waiting and seemed to know who he was. He said, “Dick’s inside there, in the autopsy room.”

Ryan was thinking he wasn’t ready for this. It was too sudden, with no time to prepare. Unless he’d be looking through a window. They probably wouldn’t let him in the room. Or it would be like an operation and he wouldn’t be able to see what was going on anyway.

They passed through a door into an anteroom. An attendant with a clipboard moved aside. A middleaged man and woman, facing the door as Ryan entered, were staring up at the wall. Neither moved. Ryan looked around as he edged past them.

There was a television monitor mounted high on the wall, angled down. On the screen was a black-and-white picture of a young woman’s face, her eyes closed.

Going through a fire door into a narrow hallway, Ryan said, “What was going on there?”

The uniformed cop said over his shoulder, “Identifying a body. It’s not as much of a shock that way.”

“She seemed young,” Ryan said. “The girl.”

He was aware of an odor now. It seemed familiar. It wasn’t antiseptic, which he expected, but the opposite. He thought of it as a wet smell, something old and damp. But a human smell. It was awful and it was getting heavier.

There should have been a sign that said Warning, here it comes, or something.

He wasn’t at all ready for the first body he saw, turning a corner, walking close past a metal table, and realizing, Jesus, it was a woman. There was her thing. An old black woman with white hair.

Purple-brown skin that didn’t look like skin, peeling, decomposing to tan marble. Attached to her big toe, facing up, was a tag that bore a case number, a name and address, written in blue ink. She was right there, her body, but she didn’t seem real.

None of the bodies did, and he wasn’t aware of them immediately as human bodies. They were in the open, exposed, in the examining room and the connecting halls and alcoves. They weren’t pulled solemnly out of a wall, covered with a sheet. They lay naked on metal tray tables waiting, as though with a purpose, waiting to be put to use. Waiting to dress a theatrical scene or a store window. Coming on them suddenly, they were props. Plastic figures fashioned in detail with fingernails and pubic hair, pale breasts made of rubber, tags on their toes and brown paper bags between lower legs, stuffed with clothing. Some were composed, at rest, with arms extended; the hands of a young black man at his penis, as if about to relieve himself. And some were contorted in shapes of anguish, limbs bent awkwardly, hands raised, clutching something that was no longer there, with pink traces of blood smeared on plastic skin. Ryan, at first, tried not to look closely at the wounds, at the slashes and punctures, and moved his gaze quickly from the sudden shocking wounds, the stump of a leg, a face torn away. But he would look again, gradually, taking it a little at a time and deciding he felt all right and wasn’t going to be sick. He could look, because what had been a person inside, making the body human, was no longer there.

A television camera on a raised platform aimed its lens on the sleeping girl Ryan had seen on the monitor. There were no traces of blood that had been wiped away, no marks or blemishes on her body, except for a small tattoo above her left breast, a heart and a name that Ryan couldn’t read. As he stared at her, the uniformed cop said, “Suicide. Apparent. She took forty-five Darvon.” Ryan nodded, aware of the odor, not wanting to breathe it in. It was familiar, but he couldn’t think of what it was. Something he remembered from when he was a kid.

Charlie Martz and Other Stories: The Unpublished Stories

Charlie Martz and Other Stories: The Unpublished Stories Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #2

Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #2 Fire in the Hole

Fire in the Hole Tishomingo Blues (2002)

Tishomingo Blues (2002) Djibouti

Djibouti When the Women Come Out to Dance: Stories

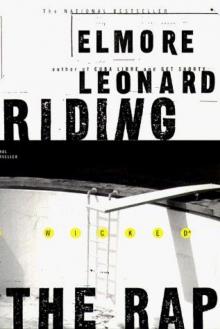

When the Women Come Out to Dance: Stories Riding the Rap

Riding the Rap Moment of Vengeance and Other Stories

Moment of Vengeance and Other Stories Raylan

Raylan Touch

Touch Mr Majestyk

Mr Majestyk Swag

Swag Road Dogs

Road Dogs La Brava

La Brava The Hot Kid

The Hot Kid Valdez Is Coming: A Novel

Valdez Is Coming: A Novel Be Cool

Be Cool The Law at Randado

The Law at Randado The Bounty Hunters

The Bounty Hunters When the Women Come Out to Dance

When the Women Come Out to Dance 310 to Yuma and Other Stories (1953)

310 to Yuma and Other Stories (1953) Tishomingo Blues

Tishomingo Blues Cat Chaser

Cat Chaser Pagan Babies

Pagan Babies Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #1

Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #1 52 Pickup

52 Pickup Stick

Stick The Moonshine War

The Moonshine War Valdez Is Coming

Valdez Is Coming City Primeval

City Primeval Rum Punch

Rum Punch Out of Sight

Out of Sight Naked Came the Manatee (1996)

Naked Came the Manatee (1996) Killshot

Killshot Cuba Libre

Cuba Libre Forty Lashes Less One

Forty Lashes Less One The Complete Western Stories of Elmore Leonard

The Complete Western Stories of Elmore Leonard Pronto

Pronto Split Images

Split Images Last Stand at Saber River

Last Stand at Saber River The Switch

The Switch Three-Ten to Yuma and Other Stories

Three-Ten to Yuma and Other Stories Bandits

Bandits Comfort to the Enemy and Other Carl Webster Stories

Comfort to the Enemy and Other Carl Webster Stories Hombre

Hombre Trail of the Apache and Other Stories

Trail of the Apache and Other Stories LaBrava

LaBrava Gold Coast

Gold Coast Jackie Brown

Jackie Brown Escape From Five Shadows

Escape From Five Shadows Karen Makes out (1996)

Karen Makes out (1996) Up in Honey's Room

Up in Honey's Room How Carlos Webster Changed His Name to Carl and Became a Famous Oklahoma Lawman (2003)

How Carlos Webster Changed His Name to Carl and Became a Famous Oklahoma Lawman (2003) Mr. Paradise

Mr. Paradise The Hunted

The Hunted Freaky Deaky

Freaky Deaky Louly and Pretty Boy (Ss)

Louly and Pretty Boy (Ss) Glitz

Glitz A Coyote's in the House

A Coyote's in the House The Big Bounce jr-1

The Big Bounce jr-1 Up in Honey's Room cw-2

Up in Honey's Room cw-2 Unknown Man #89 jr-3

Unknown Man #89 jr-3 Get Shorty: A Novel cp-1

Get Shorty: A Novel cp-1 Gunsights

Gunsights Riding the Rap rg-2

Riding the Rap rg-2