- Home

- Elmore Leonard

LaBrava

LaBrava Read online

ELMORE

LEONARD

LABRAVA

This one’s for Swanie,

bless his heart.

Contents

The Extras

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

About the Author

Praise and Acclaim

Books by Elmore Leonard

Copyright

About the Publisher

1

* * *

“HE’S BEEN TAKING PICTURES three years, look at the work,” Maurice said. “Here, this guy. Look at the pose, the expression. Who’s he remind you of?”

“He looks like a hustler,” the woman said.

“He is a hustler, the guy’s a pimp. But that’s not what I’m talking about. Here, this one. Exotic dancer backstage. Remind you of anyone?”

“The girl?”

“Come on, Evelyn, the shot. The feeling he gets. The girl trying to look lovely, showing you her treasures, and they’re not bad. But look at the dressing room, all the glitzy crap, the tinfoil cheapness.”

“You want me to say Diane Arbus?”

“I want you to say Diane Arbus, that would be nice. I want you to say Duane Michaels, Danny Lyon. I want you to say Winogrand, Lee Friedlander. You want to go back a few years? I’d like very much for you to say Walker Evans, too.”

“Your old pal.”

“Long, long time ago. Even before your time.”

“Watch it,” Evelyn said, and let her gaze wander over the eight-by-ten black and white prints spread out on the worktable, shining in fluorescent light.

“He’s not bad,” Evelyn said.

Maurice sighed. He had her interest.

“He’s got the eye, Evelyn. He’s got an instinct for it, and he’s not afraid to walk up and get the shot. I’ll tell you something else. He’s got more natural ability than I had in sixty years taking pictures. He’s been shooting maybe four.”

Evelyn said, “Let’s see, what does that make you, Maury? You still seventy-nine?”

“Probably another couple years,” Maurice said. “Till I get tired of it.” Maurice Zola: he was five-five, weighed about one-fifteen and spoke with a soft urban-south accent that had wise-guy overtones, decades of street-corner styles blended and delivered, right or wrong, with casual authority. Thirty-five years ago this red-headed woman had worked for him when he had photo concessions in some of the big Miami Beach hotels and nightclubs. Evelyn Emerson—he’d tell her he loved the sound of her name, it was lyrical, and he’d sing it taking her to bed; though never to the same tune. Now she had her own business, the Evelyn Emerson Gallery in Coconut Grove and outweighed him by fifty pounds.

Evelyn said, “I sure don’t need any art deco, impressionistic angles. The kids like it, but they don’t buy.”

“What art deco?” Maurice looked over the worktable, picked out a print. “He shoots people. Here, the old Jewish broads sitting on the porch—sure, you’re gonna get some of the hotel. The hotel’s part of the feeling. These people, time has passed them by. Here, Lummus Park. They look like a flock of birds, uh? The nose shields, like beaks.”

“Old New York Jews and Cubans,” Evelyn said.

“That’s the neighborhood, kid. He’s documenting South Beach like it is today. He’s getting the drama of it, the pathos. This guy, look, with the tattoos . . .”

“He’s awful looking.”

“Wants to make himself attractive, adorn his body. But you look at him closely, the guy’s feeling something, he’s a person. Gets up in the morning, has his Cheerios like everybody else.”

She said, “Well, he’s not in the same league with any number of people I could name.”

“He’s not pretentious like a lot of ’em either,” Maurice said. “You don’t see any bullshit here. He shoots barefaced fact. He’s got the feel and he makes you feel it.”

“What’s his name?”

“It’s Joseph LaBrava.”

Evelyn said, “LaBrava. Why does that sound familiar?”

She was looking at Maurice’s tan scalp as he lowered his head, peered at her over his glasses, then pushed them up on his nose: a gesture, like tipping his hat.

“Because you’re aware, you know what’s going on. Why do you think I came here instead of one of those galleries up on Kane Concourse?”

“Because you still love me. Come on—”

“Some people have to work their ass off for years to get recognition,” Maurice said. “Others, they get discovered overnight. September the second, 1935, I happen to be on Islamorada working on the Key West extension, Florida East Coast line, right?”

Evelyn knew every detail, how the ’35 hurricane tore into the keys and Maurice got pictures of the worst railroad disaster in Florida history. Two hundred and eighty-six men working on the road killed or missing . . . and two months later he was shooting pictures for the Farm Security Administration, documenting the face of America during the Depression.

She said, “Maury, who’s Joseph LaBrava?”

He was back somewhere in his mind and had to close his eyes and open them, adjusting his prop, his heavy-frame glasses.

“It was LaBrava took the shot of the guy being thrown off the overpass.”

Evelyn said, “Oh, my God.”

“Joe had come off the 79th Street Causeway going out to Hialeah. He’s approaching I-95 he sees the three guys up there by the railing.”

“That was pure luck,” Evelyn said.

“Wait. Nothing was going on yet. Three guys, they look like they’re just standing there. But he senses something and pulls off the road.”

“He was still lucky,” Evelyn said, “I mean to have a camera with him.”

“He always has a camera. He was going out to Hialeah to shoot. He looks up, sees the three guys and gets out his telephoto lens. Listen, he got off two shots before they even picked the guy up. Then he got ’em, they’re holding the guy up in the air and he got the one the guy falling, arms and legs out like he’s flying, the one that was in Newsweek and all the papers.”

“He must’ve done all right.”

“Cleared about twelve grand so far, the one shot,” Maurice said, “the one you put in your window, first gallery to have a Joseph LaBrava show.”

“I don’t know,” Evelyn said, “my trade leans more toward exotic funk. Surrealism’s big now. Winged snakes, colored smoke . . .”

“You oughta hand out purgatives with that shit, Evelyn. This guy’s for real, and he’s gonna make it. I guarantee you.”

“Is he presentable?”

“Nice looking guy, late thirties. Dark hair, medium height, on the thin side. No style, but yeah, he’s presentable.”

Evelyn said, “I see ’em come in with no socks on, I know they’ve got a portfolio full of social commentary.”

“He’s not a hippy. No, I didn’t mean to infer that.” Maurice paused, serious, about to confide. “You know the guys that guard the President? The Secret Service guys? That’s what he used to be, one of those.”

“Really?” Evelyn seemed to like it. “Well, they’re always neat looking

, wear suits and ties.”

“Yeah, he used to have style,” Maurice said. “But now, he quit getting his hair cut at the barbershop, dresses very casual. But you watch him, Joe walks down the street he knows everything that’s going on. He picks faces out of the crowd, faces that interest him. It’s a habit, he can’t quit doing it. Before he was in the Secret Service, you know what he was? He was an investigator for the Internal Revenue.”

“Jesus,” Evelyn said, “he sounds like a lovely person.”

“No, he’s okay. He’ll tell you he was in the wrong business,” Maurice said. “Now he spots an undesirable, a suspicious looking character, all he wants to do is take the guy’s picture.”

“He sounds like a character himself,” Evelyn said.

“I suppose you could say that,” Maurice said. “One of those quiet guys, you never know what he’s gonna do next . . . But he’s good, isn’t he?”

“He isn’t bad,” Evelyn said.

2

* * *

“I’M GOING TO TELL you a secret I never told anybody around here,” Maurice said, his glasses, his clean tan scalp shining beneath the streetlight. “I don’t just manage the hotel I own it. I bought it, paid cash for it in 1951. Right after Kefauver.”

Joe LaBrava said, “I thought a woman in Boca owned it. Isn’t that what you tell everybody?”

“Actually the lady in Boca owns a piece of it. ‘Fifty-eight she was looking for an investment.” Maurice Zola paused. “ ‘Fifty-eight or it might’ve been ’59. I remember they were making a movie down here at the time. Frank Sinatra.”

They had come out of the hotel, the porch lined with empty metal chairs, walked through the lines of slow-moving traffic to the beach side of the street where Maurice’s car was parked. LaBrava was patient with the old man, but waiting, holding the car door open, he hoped this wasn’t going to be a long story. They could be walking along the street, the old man always stopped when he wanted to tell something important. He’d stop in the doorway of Wolfie’s on Collins Avenue and people behind them would have to wait and hear about bust-out joints where you could get rolled in the old days, or how you could tell a bookie when everybody on the beach was wearing resort outfits. “You know how?” The people behind them would be waiting and somebody would say, “How?” Maurice would say, “Everybody wore their sport shirts open usually except bookies. A bookie always had the top button buttoned. It was like a trademark.” He would repeat it a few more times waiting for a table. “Yeah, they always had that top button buttoned, the bookies.

“Edward G. Robinson was in the picture they were making. Very dapper guy.” Maurice pinched the knot of his tie, brought his hand down in a smoothing gesture over his pale blue, tropical sports jacket. “You’d see ’em at the Cardozo, the whole crew, all these Hollywood people, and at the dog track used to be down by the pier, right on First Street. No, it was between Biscayne and Harley.”

“I know . . . You gonna get in the car?”

“See, I tell the old ladies I only manage the place so they don’t bug me. They got nothing to do, sit out front but complain. Use to be the colored guys, now it’s the Cubans, the Haitians, making noise on the street, grabbing their purses. Graubers, they call ’em, momzers, loomps. ‘Run the loomps off, Morris. Keep them away from here, and the nabkas.’ That’s the hookers. I’m starting to sound like ’em, these almoonas with the dyed hair. I call ’em my bluebirds, they love it.”

“Let me ask you,” LaBrava said, leaving himself open but curious about something. “The woman we’re going to see, she’s your partner?”

“The lady we’re gonna rescue, who I think’s got a problem,” Maurice said, looking up at the hotel; one hand on the car that was an old-model Mercedes with vertical twin headlights, the car once cream-colored but now without lustre. “That’s why I mention it. She starts talking about the hotel you’ll know what she’s talking about. I owned the one next door, too, but I sold it in ’68. Somebody should’ve tied me to a toilet, wait for the real estate boom.”

“What, the Andrea? You owned that, too?”

“It used to be the Esther, I changed the name of both of ’em. Come here.” Maurice took LaBrava by the arm, away from the car. “The streetlight, you can’t see it good. All right, see the two names up there? Read ’em so they go together. What’s it say?”

There were lighted windows along the block of three- and four-story hotels, pale stucco in faded pastels, streamlined moderne facing the Atlantic from a time past: each hotel expressing its own tropical deco image in speed lines, wraparound corners, accents in glass brick, bas relief palm trees and mermaids.

“It says the Andrea,” LaBrava said, “and the Della Robbia.”

“No, it don’t say the Andrea and the Della Robbia.” Maurice held onto LaBrava’s arm, pointing now. “Read it.”

“It’s too dark.”

“I can see it you can see it. Look. You read it straight across it says Andrea Della Robbia. He was a famous Italian sculptor back, I don’t know, the fourteen, fifteen hundreds. They name these places the Esther, the Dorothy—what kind of name is that for a hotel on South Miami Beach? I mean back then. Now it don’t matter. South Bronx south, it’s getting almost as bad.”

“Della Robbia,” LaBrava said. “It’s a nice name. We going?”

“You say it, Della Robbia,” Maurice said, rolling the name with a soft, Mediterranean flourish, tasting it on his tongue, the sound giving him pleasure. “Then the son of a bitch I sold it to—how do you like this guy? He paints the Andrea all white, changes the style of the lettering and ruins the composition. See, both hotels before were a nice pale yellow, dark green letters, dark green the decoration parts, the names read together like they were suppose to.”

LaBrava said, “You think anybody ever looks up there?”

“Forget I told you,” Maurice said. They walked back to the car and he stopped again before getting in. “Wait. I want to take a camera with us.”

“It’s in the trunk.”

“Which one?”

“The Leica CL.”

“And a flash?”

“In the case.”

Maurice paused. “You gonna wear that shirt, uh?”

LaBrava’s white shirt bore a pattern of bananas, pineapples and oranges. “It’s brand new, first time I’ve had it on.”

“Got all dressed up. Who you suppose to be, Murf the Surf?”

There was a discussion when LaBrava went around the block from Ocean Drive to Collins and headed south to Fifth Street to get on the MacArthur Causeway. Maurice said, we’re going north, what do you want to go south for? Why didn’t you go up to Forty-first Street, take the Julia Tuttle? LaBrava said, because there’s traffic up there on the beach, it’s still the season. Maurice said, eleven o’clock at night? You talk about traffic, it’s nothing what it used to be like. You could’ve gone up, taken the Seventy-ninth Street Causeway. LaBrava said, you want to drive or you want me to?

They didn’t get too far on I-95 before they came to all four lanes backed up, approaching the 112 interchange, brake lights popping on and off as far ahead as they could see. Crawling along in low gear, stopping, starting, the Mercedes stalled twice.

LaBrava said, “All the money you got, why don’t you buy a new car?”

Maurice said, “You know what you’re talking about? This car’s a classic, collector’s model.”

“Then you oughta get a tune.”

Maurice said, “What do you mean, all the money I got?”

“You told me you were a millionaire one time.”

“Used to be,” Maurice said. “I spent most of my dough on booze, broads and boats and the rest I wasted.”

Neither of them spoke again until they were beyond Fort Lauderdale. They could sit without talking and LaBrava would be reasonably comfortable; he never felt the need to invent conversation. He was curious when he asked Maurice:

“What do you want the camera for?”

“Maybe I want

to take a picture.”

“The woman?”

“Maybe. I don’t know yet. I have to see how she is.”

“She a good friend of yours?”

Maurice said, “I’m going out this time of night to help somebody I don’t know? She’s a very close friend.”

“How come if she lives in Boca they took her to Delray Beach?”

“That’s where the place is they take them. It’s run by the county. Palm Beach.”

“Is it like a hospital?”

“What’re you asking me for? I never been there.”

“Well, what’d the girl say on the phone?”

“Something about she was brought in on the Meyers Act.”

“It means she was drunk.”

“That’s what I’m afraid of.”

“They pick you up in this state on a Meyers Act,” LaBrava said, “it means you’re weaving around with one eye closed, smashed. They pick you up on a Baker Act it means you’re acting weird in public and’re probably psycho. I remember that from when I was here before.”

He had spent a year and a half in the Miami field office of the United States Secret Service, one of five different duty assignments in nine years.

* * *

He had told Maurice about it one Saturday morning driving down to Islamorada, LaBrava wanting to try bonefishing and Maurice wanting to show him where he was standing when the tidal wave hit in ’35. LaBrava would remember the trip as the only time Maurice ever asked him questions, ever expressed an interest in his past life. In parts of it, anyway.

He didn’t get to tell much of the IRS part, the three years he’d worked as an investigator when he was young and eager. “Young and dumb,” Maurice said. Maurice didn’t want to hear anything about the fucking IRS.

Or much about LaBrava’s marriage, either—during the same three years—to the girl he’d met in accounting class, Wayne State University, who didn’t like to drink, smoke or stay out late, or go to the show. Though she seemed to like all those things before. Strange? Her name was Lorraine. Maurice said, what’s strange about it? They never turn out like you think they’re going to. Skip that part. There wasn’t anything anybody could tell him about married life he didn’t know. Get to the Secret Service part.

Charlie Martz and Other Stories: The Unpublished Stories

Charlie Martz and Other Stories: The Unpublished Stories Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #2

Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #2 Fire in the Hole

Fire in the Hole Tishomingo Blues (2002)

Tishomingo Blues (2002) Djibouti

Djibouti When the Women Come Out to Dance: Stories

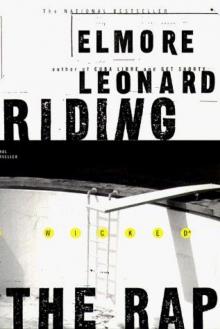

When the Women Come Out to Dance: Stories Riding the Rap

Riding the Rap Moment of Vengeance and Other Stories

Moment of Vengeance and Other Stories Raylan

Raylan Touch

Touch Mr Majestyk

Mr Majestyk Swag

Swag Road Dogs

Road Dogs La Brava

La Brava The Hot Kid

The Hot Kid Valdez Is Coming: A Novel

Valdez Is Coming: A Novel Be Cool

Be Cool The Law at Randado

The Law at Randado The Bounty Hunters

The Bounty Hunters When the Women Come Out to Dance

When the Women Come Out to Dance 310 to Yuma and Other Stories (1953)

310 to Yuma and Other Stories (1953) Tishomingo Blues

Tishomingo Blues Cat Chaser

Cat Chaser Pagan Babies

Pagan Babies Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #1

Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #1 52 Pickup

52 Pickup Stick

Stick The Moonshine War

The Moonshine War Valdez Is Coming

Valdez Is Coming City Primeval

City Primeval Rum Punch

Rum Punch Out of Sight

Out of Sight Naked Came the Manatee (1996)

Naked Came the Manatee (1996) Killshot

Killshot Cuba Libre

Cuba Libre Forty Lashes Less One

Forty Lashes Less One The Complete Western Stories of Elmore Leonard

The Complete Western Stories of Elmore Leonard Pronto

Pronto Split Images

Split Images Last Stand at Saber River

Last Stand at Saber River The Switch

The Switch Three-Ten to Yuma and Other Stories

Three-Ten to Yuma and Other Stories Bandits

Bandits Comfort to the Enemy and Other Carl Webster Stories

Comfort to the Enemy and Other Carl Webster Stories Hombre

Hombre Trail of the Apache and Other Stories

Trail of the Apache and Other Stories LaBrava

LaBrava Gold Coast

Gold Coast Jackie Brown

Jackie Brown Escape From Five Shadows

Escape From Five Shadows Karen Makes out (1996)

Karen Makes out (1996) Up in Honey's Room

Up in Honey's Room How Carlos Webster Changed His Name to Carl and Became a Famous Oklahoma Lawman (2003)

How Carlos Webster Changed His Name to Carl and Became a Famous Oklahoma Lawman (2003) Mr. Paradise

Mr. Paradise The Hunted

The Hunted Freaky Deaky

Freaky Deaky Louly and Pretty Boy (Ss)

Louly and Pretty Boy (Ss) Glitz

Glitz A Coyote's in the House

A Coyote's in the House The Big Bounce jr-1

The Big Bounce jr-1 Up in Honey's Room cw-2

Up in Honey's Room cw-2 Unknown Man #89 jr-3

Unknown Man #89 jr-3 Get Shorty: A Novel cp-1

Get Shorty: A Novel cp-1 Gunsights

Gunsights Riding the Rap rg-2

Riding the Rap rg-2