- Home

- Elmore Leonard

Pagan Babies

Pagan Babies Read online

For Jackie Farber

Contents

The Extras

Chapters:

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

About the Author

Praise and Acclaim

Books by Elmore Leonard

Copyright

About the Publisher

1

* * *

THE CHURCH HAD BECOME a tomb where forty-seven bodies turned to leather and stains had been lying on the concrete floor the past five years, though not lying where they had been shot with Kalashnikovs or hacked to death with machetes. The benches had been removed and the bodies reassembled: men, women and small children laid in rows of skulls and spines, femurs, fragments of cloth stuck to mummified remains, many of the adults missing feet, all missing bones that had been carried off by scavenging dogs.

Since the living would no longer enter the church, Fr. Terry Dunn heard confessions in the yard of the rectory, in the shade of old pines and silver eucalyptus trees.

“Bless me, Fatha, for I have sin. It has been two months from the last time I come to Confession. Since then I am fornicating with a woman from Gisenyi three times only and this is all I have done.”

They would seem to fill their mouths with the English words, pro-nounc-ing each one carefully, with an accent Terry believed was heard only in Africa. He gave fornicators ten Our Fathers and ten Hail Marys, murmured what passed for an absolution while the penitent said the Act of Contrition, and dismissed them with a reminder to love God and sin no more.

“Bless me, Fatha, for I have sin. Is a long time since I come here but is not my fault, you don’t have Confession always when you say. The sin I did, I stole a goat from close by Nyundo for my family to eat. My wife cook it en brochette and also in a stew with potatoes and peppers.”

“Last night at supper,” Terry said, “I told my housekeeper I’d enjoy goat stew a lot more if it wasn’t so goddamn bony.”

The goat thief said, “Excuse me, Fatha?”

“Those little sharp bones you get in your mouth,” Terry said, and gave the man ten Our Fathers and ten Hail Marys. He gave just about everyone ten Our Fathers and ten Hail Marys to say as their penance.

Some came seeking advice.

“Bless me, Fatha, I have not sin yet but I think of it. I see one of the men kill my family has come back. One of the Hutu Interahamwe militia, he come back from the Goma refugee camp and I like to kill him, but I don’t want to go to prison and I don’t want to go to Hell. Can you have God forgive me before I kill him?”

Terry said, “I don’t think He’ll go for it. The best you can do, report the guy to the conseiller at the sector office and promise to testify at the trial.”

The man who hadn’t killed anyone yet said, “Fatha, when is that happen? I read in Imvaho they have one hundred twenty-four thousand in prisons waiting for trials. In how many years will it be for this man that kill my family? Imvaho say two hundred years to try all of them.”

Terry said, “Is the guy bigger than you are?”

“No, he’s Hutu.”

“Walk up to the guy,” Terry said, “and hit him in the mouth as hard as you can, with a rock. You’ll feel better. Now make a good Act of Contrition for anything you might’ve done and forgot about.” Terry could offer temporary relief but nothing that would change their lives.

Penitents would kneel on a prie-dieu and see his profile through a framed square of cheesecloth mounted on the kneeler: Fr. Terry Dunn, a bearded young man in a white cassock, sitting in a wicker chair. Sideways to the screen he looked at the front yard full of brush and weeds and the road that came up past the church from the village of Arisimbi. He heard Confession usually once a week but said Mass, in the school, only a few times a year: Christmas Day, Easter Sunday and when someone died. The Rwandese Bishop of Nyundo, nine miles up the road, sent word for Fr. Dunn to come and give an account of himself.

He drove there in the yellow Volvo station wagon that had belonged to the priest before him and sat in the bishop’s office among African sculptures and decorative baskets, antimacassars in bold star designs on the leather sofa and chairs, on the wall a print of the Last Supper and a photograph of the bishop taken with the pope. Terry had worn his cassock. The bishop, in a white sweater, asked him if he was attempting to start a new sect within the Church. Terry said no, he had a personal reason for not acting as a full-time priest, but would not say what it was. He did tell the bishop, “You can contact the order that runs the mission, the Missionary Fathers of St. Martin de Porres in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, and ask to have me replaced; but if you do, good luck. Young guys today are not breaking down the door to get in the seminary.”

This was several years ago. Terry left the bishop shaking his head and was still here on his own.

This afternoon the prie-dieu was placed beneath a roof of palm fronds and thatch that extended from the rectory into the yard. A voice raised against the hissing sound of the rain said, “Bless me, Fatha, for I have sin,” and started right in. “I kill seven people that time I’m still a boy and we kill the inyenzi, the cockroaches. I kill four persons in the church the time you saying the Mass there and you see it happen. You know we kill five hundred in Nyundo before we come here and kill I think one hundred in this village before everybody run away.”

Terry continued to stare at the yard that sloped down to the road, the clay hardpack turned dark in the rain.

“And we kill some more where we have the roadblock and stop all the drivers and look at the identity cards. The ones we want we take in the bush and kill them.”

The man paused and Terry waited. The guy wasn’t confessing his sins, he was bragging about what he did.

“You hear me, Fatha?”

Terry said, “Keep talking,” wondering where the guy was going with it.

“I can tell you more will die very soon. How do I know this? I am a visionary, Fatha. I am told in visions of the Blessed Virgin saying to do it, to kill the inyenzi. I tell you this and you don’t say nothing, do you?”

Terry didn’t answer. The man’s voice, at times shrill, sounded familiar.

“No, you can’t,” the voice said. “Oh, you can tell me not to do it, but you can’t tell no other person, the RPA, the conseiller, nobody, because I tell you this in Confession and you have the rule say you can’t talk about what you hear. You listen to me? We going to cut the feet off before we kill them. You know why we do it? You are here that time, so you understand. But you have no power, so you don’t stop us. Listen, if we see you when we come, a tall one like you, we cut your feet off, too.”

Terry sat in his wicker chair staring out at the rain, the pale sky, mist covering the far hills. The thing was, these guys could do it. They already had, so it wasn’t just talk, the guy mouthing off.

He said, “You going to give me my penance to say?”

Terry didn’t answer.

“All right, I finished.”

The man rose from the kneeler and in a moment Terry watched him walking away, barefoot, skinny bare legs, a stick figure wearing a checker

ed green shirt and today in the rain a raggedy straw hat with the brim turned down. Terry didn’t need to see the guy’s face. He knew him the way he knew people in the village by the clothes they wore, the same clothes they put on every morning, if they didn’t sleep in them. He had seen that green shirt recently, only a few days ago . . .

* * *

Among the stalls in the marketplace.

This one wearing the shirt and three of his friends drinking banana beer from a tin trough, the trough long enough for all four of them squatting around it to stick reed straws into the thick brew, lower their heads and suck it up warm, the beer giving them a glow that showed in dreamy eyes looking up at Terry walking past the open stall, Terry catching the look and the one in the green shirt commenting as the others laughed, his voice louder then, shrill, following Terry to a man who was roasting corn in a pan of hot coals. This was Thomas, wearing a yellow T-shirt Terry had given him some months before. He asked Thomas about the guy with the shrill voice and Thomas said, “Oh, the visionary, Bernard. He drinks banana beer and our Blessed Mother speaks to him. Some people believe him.”

“What’s he saying?”

“As you go by, ‘Oh, here comes umugabo wambaye ikanzu,’ calling you ‘the man who wears a dress.’ Then he say you come to buy the food your Tutsi whore cooks for you, the one you are fucking but don’t want nobody to know it, you being a priest. Bernard say the Blessed Mother told him what you doing. Now he say he isn’t afraid of you. ‘Oli enyamaswa.’ You were sired by animals.”

“I don’t even know him. What’s he up to?”

“He talks to dishonor you in front of the people here. He calls you ‘injigi.’ “ Thomas shrugged. “Telling everyone you stupid.” Thomas raised his face in the sunlight as he listened again. On the front of his T-shirt were the words the stone coyotes, and on the back, rock with a twang. “Now he tells everyone he saw you and you saw him, but you don’t do nothing.”

“When did I see him?”

“I think he means during the genocide time, when he’s in the Hutu militia and can kill anybody he wants to. I wasn’t here or I think I would be dead.” Then Thomas said to Terry that day in the market, “But you, Fatha, you were here, hmmm? In the church when they come in there?”

“That was five years ago.”

“Look,” Thomas said, “the visionary is leaving. See how they all have machetes? They like to do it again, kill the Tutsis they miss the first time.”

Terry watched the green shirt walking away.

Today he watched from the wicker chair, the green shirt on the stick figure walking toward the road in the rain, still in the yard when Terry called to him.

“Hey, Bernard?”

It stopped him.

“I have visions, too, man.”

Francis Dunn heard from his brother no more than three or four times a year. Fran would wire funds to the Banque Commerciale du Rwanda, send a load of old clothes and T-shirts, a half-dozen rolls of film, and a month or so later Terry would write to thank him. He’d mention the weather, going into detail during the rainy season, and that would be it. He never sent pictures. Fran said to his wife, Mary Pat, “What’s he do with all the film I send him?”

Mary Pat said, “He probably trades it for booze.”

Terry hadn’t said much about the situation over there since the time of the genocide, when the ones in control then, the Hutus, closed their borders and tried to wipe out the entire Tutsi population, murdering as many as eight hundred thousand in a period of three months: a full-scale attempt at genocide that barely made the six o’clock news. Terry didn’t say much about his work at the mission, either, what he was actually doing. Fran liked to picture Terry in a white cassock and sandals gathering children around him, happy little native kids showing their white teeth.

Lately, Terry had opened up a little more, saying in a letter, “The tall guys and the short guys are still giving each other dirty looks, otherwise things seem to be back to what passes for normal here. I’ve learned what the essentials of life are. Nails, salt, matches, kerosene, charcoal, batteries, Fanta soda, rolling paper and Johnnie Walker red, the black label for a special occasion. Electricity is on in the village until about ten p.m. But there is still only one telephone. It rings in the sector office, occupied by the RPA, the Rwandese Patriotic Army, pretty good guys for a change acting as police.”

There was even a second page to the latest letter. Fran said to Mary Pat, “Listen to this. He lists the different smells you become aware of in the village, like the essence of the place. Listen. He says, ‘The smell of mildew, the smell of raw meat, cooking oil, charcoal-burning fires, the smell of pit latrines, the smell of powdered milk in the morning—people eating their gruel. The smell of coffee, overripe fruit, eucalyptus in the air. The smell of tobacco, unwashed bodies, and the smell of banana beer on the breath of a man confessing his sins.’ ”

Mary Pat said, “Gross.”

“Yeah, but you know something,” Fran said, “he’s starting to sound like himself again.”

Mary Pat said, “Is that good or bad?”

2

* * *

THE RPA OFFICER IN CHARGE took the call from the priest’s brother in America, asking how he could be of service. He placed his hand over his ear away from the receiver as he listened. He said oh, he was very sorry to hear that. Said yes, of course, he would tell Fr. Dunn. What? . . . No, the sound was rain coming down on the roof, a metal roof. Yes, only rain. This month it rained every afternoon, sometimes all day. He said hmmmm, mmm-hmm, as he listened to the priest’s brother repeat everything he had said before. Finally the RPA officer said yes, of course, he would go at once.

Then remembered something. “Oh, and a letter from you also came today.”

The priest’s brother said, “With some news he’ll be very happy to hear. Unlike this call.”

The officer’s name was Laurent Kamweya.

He was Tutsi, born in Rwanda but had lived most of his life in Uganda, where the official language was English. Laurent had gone to university in Kampala, trained with guerrilla forces of the Rwandese Patriotic Front, and returned with the army to retake the government from the Hutu génocidaires. He had been here in Arisimbi less than a year as acting conseiller, the local government official. Laurent waited until the rain had worn itself out and the tea plantations on the hills to the east were again bright green, then waited a little more.

An hour before sunset, when the priest would be sitting outside with his bottle of Johnnie Walker, Laurent got behind the wheel of the RPA’s Toyota Land Cruiser and started up the hill—maybe to learn more about this strange priest, though he would rather be going to Kigali, a place to meet smart-looking women in the hotel bars.

This was a primitive place where people drank banana beer and spent their lives as peasants hoeing the ground, digging, chopping, gathering, growing corn and beans, bananas, using all the ground here, the smallest plots, growing corn even in this road and up close to their dwellings, the houses made of mud bricks the same reddish color as the red-clay road Laurent followed, continuing up the slope to the school and the sweet potato field the children worked. Now the road switched back to come around above the school and Laurent was approaching the church, this old white basilica St. Martin de Porres, losing its paint, scars showing its mud bricks, swifts flying in and out of the belfry. A church full of ghosts, no longer of use to the living.

The road looped and switched back again above the church and now he was approaching the rectory, in the trees that grew along the crest of the hill.

There it was, set back from the road, a bungalow covered in vines, its whitewash chipped and peeling, the place uncared for, Laurent was told, since the old priest who was here most of his life had died.

And there was the priest who remained, Fr. Terry Dunn, in the shade of the thatched roof that extended from the side of the house like a room without walls, where he sat sometimes to hear Confession and in the evening with his Johnni

e Walker. Laurent had heard he also smoked ganja his housekeeper obtained for him in Gisenyi, at the Café Tum Tum Bikini. The Scotch he purchased by the case in Kigali, on his trips to the capital.

You could see from his appearance, the shorts, the T-shirts that bore the names of rock bands or different events in America, he made no effort to look like a priest. The beard could indicate he was a foreign missionary, a look some of them affected. What did he do? He distributed clothes sent by his brother, he heard Confession when he felt like it, listened to people complain of their lives, people mourning the extinction of their families. He did play with the children, took pictures of them and read to them from the books of a Dr. Seuss. But most of the time, Laurent believed, he sat here on his hill with his friend Mr. Walker.

There, looking this way, the priest getting up from the table as he sees the Land Cruiser of the Rwandese Patriotic Army come to visit, turning into the yard, to stop behind the priest’s yellow Volvo station wagon, an old one. Laurent switched off the engine and heard music, the sound coming from the house, not loud but a pleasing rhythm he believed was . . . Yes, it was reggae.

And there was the priest’s housekeeper, Chantelle, coming from the bungalow with a bowl of ice and glasses on a round tray. Chantelle Nyamwase. She brought the bottle of Scotch under her arm—actually, pressed between her slender body in a white undershirt and the stump of her arm, the left one, that had been severed just above the elbow. Chantelle seldom covered the stump. She said it told who she was, though anyone could look at her figure and see she was Tutsi. There were people who said she had worked as a prostitute at the Hotel des Mille Collines in Kigali, but could no longer perform this service because of her mutilation. With the clean white undershirt she wore a pagne smooth and tight about her hips, the skirt falling to her white tennis shoes, the material in a pattern of shades, blue and tan with streaks of white.

Charlie Martz and Other Stories: The Unpublished Stories

Charlie Martz and Other Stories: The Unpublished Stories Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #2

Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #2 Fire in the Hole

Fire in the Hole Tishomingo Blues (2002)

Tishomingo Blues (2002) Djibouti

Djibouti When the Women Come Out to Dance: Stories

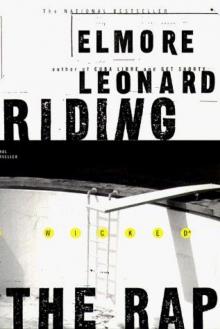

When the Women Come Out to Dance: Stories Riding the Rap

Riding the Rap Moment of Vengeance and Other Stories

Moment of Vengeance and Other Stories Raylan

Raylan Touch

Touch Mr Majestyk

Mr Majestyk Swag

Swag Road Dogs

Road Dogs La Brava

La Brava The Hot Kid

The Hot Kid Valdez Is Coming: A Novel

Valdez Is Coming: A Novel Be Cool

Be Cool The Law at Randado

The Law at Randado The Bounty Hunters

The Bounty Hunters When the Women Come Out to Dance

When the Women Come Out to Dance 310 to Yuma and Other Stories (1953)

310 to Yuma and Other Stories (1953) Tishomingo Blues

Tishomingo Blues Cat Chaser

Cat Chaser Pagan Babies

Pagan Babies Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #1

Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #1 52 Pickup

52 Pickup Stick

Stick The Moonshine War

The Moonshine War Valdez Is Coming

Valdez Is Coming City Primeval

City Primeval Rum Punch

Rum Punch Out of Sight

Out of Sight Naked Came the Manatee (1996)

Naked Came the Manatee (1996) Killshot

Killshot Cuba Libre

Cuba Libre Forty Lashes Less One

Forty Lashes Less One The Complete Western Stories of Elmore Leonard

The Complete Western Stories of Elmore Leonard Pronto

Pronto Split Images

Split Images Last Stand at Saber River

Last Stand at Saber River The Switch

The Switch Three-Ten to Yuma and Other Stories

Three-Ten to Yuma and Other Stories Bandits

Bandits Comfort to the Enemy and Other Carl Webster Stories

Comfort to the Enemy and Other Carl Webster Stories Hombre

Hombre Trail of the Apache and Other Stories

Trail of the Apache and Other Stories LaBrava

LaBrava Gold Coast

Gold Coast Jackie Brown

Jackie Brown Escape From Five Shadows

Escape From Five Shadows Karen Makes out (1996)

Karen Makes out (1996) Up in Honey's Room

Up in Honey's Room How Carlos Webster Changed His Name to Carl and Became a Famous Oklahoma Lawman (2003)

How Carlos Webster Changed His Name to Carl and Became a Famous Oklahoma Lawman (2003) Mr. Paradise

Mr. Paradise The Hunted

The Hunted Freaky Deaky

Freaky Deaky Louly and Pretty Boy (Ss)

Louly and Pretty Boy (Ss) Glitz

Glitz A Coyote's in the House

A Coyote's in the House The Big Bounce jr-1

The Big Bounce jr-1 Up in Honey's Room cw-2

Up in Honey's Room cw-2 Unknown Man #89 jr-3

Unknown Man #89 jr-3 Get Shorty: A Novel cp-1

Get Shorty: A Novel cp-1 Gunsights

Gunsights Riding the Rap rg-2

Riding the Rap rg-2