- Home

- Elmore Leonard

The Complete Western Stories of Elmore Leonard

The Complete Western Stories of Elmore Leonard Read online

the Complete Western Stories Of Elmore Leonard (2004)

Leonard, Elmore

Unknown publisher (2011)

* * *

The Complete Western Stories Of (2004)

ELMORE LEONARD

*

CONTENTS:

A Conversation with ELMORE LEONARD.

Trail of the Apache.

Apache Medicine.

You Never See Apaches . . ..

Red Hell Hits Canyon Diablo.

The Colonel's Lady.

Law of the Hunted Ones.

Cavalry Boots.

Under the Friar's Ledge.

The Rustlers.

Three-Ten to Yuma.

The Big Hunt.

Long Night.

The Boy Who Smiled.

The Hard Way.

The Last Shot.

Blood Money.

Trouble at Rindo's Station.

Saint with a Six-Gun.

The Captives.

No Man's Guns.

The Rancher's Lady.

Jugged.

Moment of Vengeance.

Man with the Iron Arm.

The Longest Day of His Life.

The Nagual.

The Kid.

Only Good Ones.

The Tonto Woman.

Hurrah for Captain Early!

*

*

Chapter 1 A Conversation with ELMORE LEONARD.

ELMORE JOHN LEONARD, Jr., started his life of writing in the fifth grade, when as a student at Blessed Sacrament Grade School in Detroit, he was inspired by a Detroit Times serialization of All Quiet on the Western Front, wrote a play, and staged it at school, the classroom desks serving as no man's land. He did not write again until his college years at the University of Detroit, where he majored in English. He wrote a few experimental short stories while spending most of his free time reading and going to the movies. "I was discovering who I liked to read," he said. "I wasn't reading for story, I was reading for style."

Sometime shortly after college Elmore decided he wanted to be a writer. "I looked for a genre where I could learn how to write and be selling at the same time," he recalls. "I chose Westerns because I liked Western movies. From the time I was a kid I liked them. Movies like The Plainsman with Gary Cooper in 1936 up through My Darling Clementine and Red River in the late forties."

There was a surge of interest in Western stories in the early fifties, Elmore notes, "from Saturday Evening Post and Colliers down through Argosy, Adventure, Blue Book, and probably at least a dozen pulp magazines, the better ones like Dime Western and Zane Grey Magazine paying two cents a word."

His first attempt at writing a Western was not a success. "I wrote about a gunsmith that made a certain kind of gun. I have no idea now what the story was about when I sent it to a pulp magazine and it was rejected. I decided I'd better do some research. I read On the Border with Crook, The Truth about Geronimo, The Look of the West, and Western Words, and I subscribed to Arizona Highways. It had stories about guns--I insisted on authentic guns in my stories--stagecoach lines, specific looks at different little facets of the West, plus all the four-color shots that I could use for my descriptions, things I could put in and sound like I knew what I was talking about."

He distilled all this valuable detail into a ledger book, which became a constant reference for his story writing throughout the decade.

Properly armed with a sense of the West, he wrote his first Western, Tizwin, the Apache name for corn beer. It didn't sell immediately. "The editor at Argosy passed it on to one of their pulp magazines at Popular Publications," Elmore remembers, "and they bought it." And changed the title to "Red Hell Hits Canyon Diablo." "The Argosy editor said, 'If you have anything else about this period, we'd like to read it.' So I sat down and wrote 'Trail of the Apache,' which was the first one that was published."

A growing family and a full-time job as a copywriter on the Chevrolet account at Campbell-Ewald Advertising in Detroit did not give Elmore a lot of time to write.

"I realized that I was going to have to get up at five in the morning if I wanted to write fiction. It took a while, the alarm would go off and I'd roll over. Finally I started to get up and go into the living room and sit at the coffee table with a yellow pad and try to write two pages. I made a rule that I had to get something down on paper before I could put the water on for the coffee. Know where you're going and then put the water on. That seemed to work because I did it for most of the fifties."

He'd also get a little writing done at the agency. "I'd put my arm in the drawer and have the tablet in there and I'd just start writing and if somebody came in I'd stop writing and close the drawer."

Elmore began to focus on a particular area of the West for his stories. "I liked Arizona and New Mexico," he said. "I didn't care that much for the High Plains Indians, I liked the Apaches because of their reputation as raiders and the way they dressed, with a headband and high moccasins up to their knees. I also liked their involvement with things Mexican and their use of Spanish names and words."

The Complete Western Stories begins with Elmore's first five shorts: Apache and cavalry stories set in Arizona in the 1870s and '80s.

"I was disappointed by rejections from the better-paying magazines, The Saturday Evening Post and Colliers," Elmore says. "They felt my stories were too relentless and lacked lighter moments or comic relief. But I continued to write what pleased me while trying to improve my style."

The next direction for Elmore's writing was obvious: write a Western novel. The result was The Bounty Hunters (1953), the prototype for many an Western. Take the most dangerous Apache, the wisest scout, and the greediest outlaw, put them all together in the desert sun, and see who wins.

As he spun out novels and short stories from five to seven in the morning, Hollywood came calling and bought a Dime Western story, "Three-Ten to Yuma," and from Argosy, "The Captives," filmed as The Tall T. Elmore was excited but in both cases "saw how easily Hollywood could screw up a simple story." Both films, released in 1957, are now regarded as minor classics.

Elmore reached his goal as a Western writer in April of 1956, when The Saturday Evening Post published his story "Moment of Vengeance."

In less than five years he had entered the pantheon of Western writers. But the Western was on its way out. "Television killed the Western,"

Elmore says. "The pulps were mostly gone by then too, the market was drying up."

In 1960, Elmore took his profit sharing from Campbell-Ewald--

$11,500--with the intention of becoming a full-time writer. He had put his ten years in. "The money would have lasted six months, and in that time I could write a book and sell it." Instead, the family bought a house and he wrote freelance advertising copy and educational films to pay the bills until the movie version of his novel Hombre was bought by a studio in 1966, and he finally had the money to write his first nonWestern novel, The Big Bounce.

But he wasn't through with the Westerns by any means. He had yet to write what many consider to be his masterpiece.

Just before his five-year fiction-writing hiatus, in 1961, he wrote a story for Roundup, a Western Writers of America anthology, called "Only Good Ones," the story of Bob Valdez, soon to be the classic hero who is misjudged by the antagonist, "the bad guys realizing too late they'll be lucky to get out of this alive."

Six years later, in search of an idea for a novel he could sell to the movies, Elmore picked up "Only Good Ones" and, in seven weeks, expanded it into Valdez Is Coming (1970) which was brought to the big screen with Burt Lancaster three years later.

"Look what I got away wit

h," Elmore says. "In the final scene of Valdez there is no shootout, not even in the film version. Writing this one I found that I could loosen up, concentrate on bringing the characters to life with recognizable traits, and ignore some of the conventions found in most Western stories."

The Complete Western Stories of charts the evolution of Elmore's style and particular sound from the very beginning of his writing career. In five years, between 1951 and 1956, he wrote twenty-seven of the thirty stories in this volume. He carved out his turf in the Arizona and New Mexico Territories, from Bisbee to Contention, from Yuma Territorial Prison to the Jicarilla Apache Subagency in Puerco, creating dozens of memorable characters: good, bad, and really bad. (Those are the ones we like the most.)

Elmore Leonard wrote a total of eight Western novels before, during, and after his Complete Western Stories; he even wrote a few Western stories contained herein, after he began writing contemporary crime novels ("The Tonto Woman" and " 'Hurrah for Captain Early!' ").

Over time, the suffocating heat and alkali dust of the Arizona desert gave way to the mean streets of Detroit and the subtropical weirdness of South Florida. But Elmore will be the first to tell you, they're all derived from what he learned writing these Western stories; he just changed the setting and the century.

--gregg sutter, los angeles, 2004

*

*

Chapter 1 Trail of the Apache.

Original title: Apache Agent.

Argosy, December 1951.

UNDER THE THATCHED roof ramada that ran the length of the agency office, Travisin slouched in a canvas-backed chair, his boots propped against one of the support posts. His gaze took in the sun-beaten, gray adobe buildings, all one-story structures, that rimmed the vacant quadrangle. It was a glaring, depressing scene of sun on rock, without a single shade tree or graceful feature to redeem the squat ugliness. There was not a living soul in sight. Earlier that morning, his White Mountain Apache charges had received their two-weeks' supply of beef and flour.

By now they were milling about the cook fires in front of their wickiups, eating up a two-weeks' ration in two days. Most of the Indians had built their wickiups three miles farther up the Gila, where the flat, dry land began to buckle into rock-strewn hills. There the thin, sparse Gila cottonwoods grew taller and closer together and the mesquite and prickly pear thicker. And there was the small game that sustained them when their government rations were consumed.

At the agency, Travisin lived alone. By actual count there were forty-two Coyotero Apache scouts along with the interpreter, Barney Fry, and his wife, a Tonto woman, but as the officers at Fort Thomas looked at it, he was living alone. There is no question that to most young Eastern gentlemen on frontier station, such an alien means of existence would have meant nothing more than a very slow way to die, with boredom reading the services. But, of course, they were not Travisin.

FROM WHIPPLE BARRACKS, through San Carlos and on down to Fort Huachuca, it went without argument that Eric Travisin was the best Apache campaigner in Arizona Territory. There was a time, of course, when this belief was not shared by all and the question would pop up often, along the trail, in the barracks at Fort Thomas, or in a Globe barroom.

Barney Fry's name would always come up then--though most discounted him for his one-quarter Apache blood. But that was a time in the past when Eric Travisin was still new; before the sweltering sand-rock Apache country had burned and gouged his features, leaving his gaunt face deepchiseled and expressionless. That was while he was learning that it took an Apache to catch an Apache. So, for all practical purposes, he became one.

Barney Fry taught him everything he knew about the Apache; then he began teaching Fry. He relied on no one entirely, not even Fry. He followed his own judgment, a judgment that his fellow officers looked upon as pure animal instinct. And perhaps they were right. But Travisin understood the steps necessary to survival in an enemy element. They weren't included in Cook's "Cavalry Tactics": you learned them the hard way, and your being alive testified that you had learned well. They said Travisin was more of an Apache than the Apaches themselves. They said he was cold-blooded, sometimes cruel. And they were uneasy in his presence; he had discarded his cotillion demeanor the first year at Fort Thomas, and in its place was the quiet, pulsing fury of an Apache war dance.

This was easy enough for the inquisitive to understand. But there was another side to Eric Travisin.

For three years he had been acting as agent at the Camp Gila subagency, charged with the health and welfare of over two hundred White Mountain Apaches. And in three years he had transformed nomadic hostiles into peaceful agriculturalists. He was a dismounted cavalry officer who sometimes laid it on with the flat of his saber, but he was completely honest. He understood them and took their side, and they respected him for it. It was better than San Carlos.

That's why the conversation at the officers' mess at Fort Thomas, thirty miles southwest, so often dwelled on him: he was a good Samaritan with a Spencer in his hand. They just didn't understand him. They didn't realize that actually he was following the line of least resistance. He was accepting the situation as it was and doing the best job with the means at hand. To Travisin it was that simple; and fortunately he enjoyed it, both the fighting and the pacifying. The fact that it made him a better cavalryman never entered his mind. He had forgotten about promotions. By this time he was too much a part of the savage everyday existence of Apache country. He looked at the harsh, rugged surroundings and liked what he saw.

He shuffled his feet up and down the porch pole and sank deeper into his camp chair. Suddenly in his breast he felt the tenseness. His ears seemed to tingle and strain against an unnatural stillness, and immediately every muscle tightened. But as quickly as the strange feeling came over him, he relaxed. He moved his head no more than two inches, and from the corner of his eye saw the Apache crouched on hands and knees at the corner of the ramada. The Indian crept like an animal across the porch, slowly and with his back arched. A pistol and a knife were at his waist, but he carried no weapon in his hands. Travisin moved his right hand across his stomach and eased open the holster flap. Now his arms were folded across his chest, with his right hand gripping the holstered pistol. He waited until the Apache was less than six feet away before he wheeled from his chair and pushed the longbarreled revolving pistol into the astonished Apache's face.

Travisin grinned at the Apache and holstered the handgun. "Maybe someday you'll do it."

The Indian grunted angrily. With victory almost in his grasp he had failed again. Gatito, sergeant of Travisin's Apache scouts, was an old man, the best tracker in the Army, and it cut his pride deeply that he was never able to win their wager. Between the two men was an unusual bet of almost two years' standing. If at any time, while not officially occupied, the scout was able to steal up to the officer and place his knife at Travisin's back, a bottle of whiskey was his. For such a prize the Indian would gladly crawl through anything. He tried constantly, using every trick he knew, but the officer was always ready. The result was a grumbling, thirsty Indian, but an officer whose senses were razor-sharp.

Travisin even practiced staying alive.

Gatito gave the report of the morning patrol and then added, almost as an afterthought, "Chiricahua come. Two miles away."

Travisin wheeled from the office doorway. "Where?" Gatito spoke impassively. "Chiricahua come. He come with troop from Fort."

Travisin considered the Apache's words in silence, squinting through the afternoon glare toward the wooden bridge across the Gila that was the end of the trail from Thomas. They would come from that direction. "Go get Fry immediately. And turn out your boys."

Chapter Two.

SECOND LIEUTENANT William de Both, West Point's newest contribution to the "Dandy 5th," had the distinct feeling that he was entering a hostile camp as he led H troop across the wooden bridge and approached Camp Gila. As he drew nearer to the agency office, the figures in front of it appeared no frie

ndlier. Good God, were they all Indians? After guarding the sixteen hostiles the thirty miles from Fort Thomas, Lieutenant de Both had had enough of Indians for a long time. Even with the H troopers riding four sides, he couldn't help glancing nervously back to the sixteen hostiles and expecting trouble to break out at any moment. After thirty miles of this, he was hardly prepared to face the gaunt, raw-boned Travisin and his sinister-looking band of Apache scouts. His fellow officers back at Fort Thomas had eagerly informed de Both of the character of the formidable Captain Travisin. In fact, they painted a picture of him with bold, harsh strokes, watching the young lieutenant's face intently to enjoy the mixed emotions that showed so obviously. But even with the exaggerated tales of the officers' mess, de Both could not help learning that this unusual Indian agent was still the best army officer on the frontier. Three months out of the Point, he was only too eager to serve under the best.

Leading his troop across the square, he scanned the ragged line of men in front of the office and on the ramada. All were armed, and all stared at the approaching column as if it were bringing cholera instead of sixteen unarmed Indians. He halted the column and dismounted in front of the tall, thin man in the center. The lieutenant inspected the man's faded blue chambray shirt and gray trousers, and unconsciously adjusted his own blue jacket.

"My man, would you kindly inform the captain that Lieutenant de Both is reporting? I shall present my orders to him." The lieutenant was brushing trail dust from his sleeve as he spoke.

Travisin stood with hands on hips looking at de Both. He shook his head faintly, without speaking, and began to twist one end of his dragoon mustache. Then he nodded to the foremost of the Chiricahuas and turned to Barney Fry.

"Barney, that's Pillo, isn't it?"

"Ain't nobody else," the scout said matter-of-factly. "And the skinny buck on the paint is Asesino, his son-in-law."

Travisin turned his attention to the bewildered lieutenant. "Well, mister, ordinarily I'd play games with you for a while, but under the circumstances, when you bring along company like that, we'd better get down to the business at hand without the monkeyshines. Fry, take care of our guests. Lieutenant, you come with me." He turned abruptly and entered the office.

Charlie Martz and Other Stories: The Unpublished Stories

Charlie Martz and Other Stories: The Unpublished Stories Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #2

Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #2 Fire in the Hole

Fire in the Hole Tishomingo Blues (2002)

Tishomingo Blues (2002) Djibouti

Djibouti When the Women Come Out to Dance: Stories

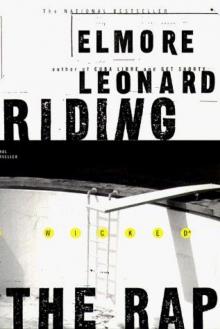

When the Women Come Out to Dance: Stories Riding the Rap

Riding the Rap Moment of Vengeance and Other Stories

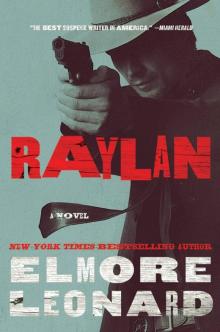

Moment of Vengeance and Other Stories Raylan

Raylan Touch

Touch Mr Majestyk

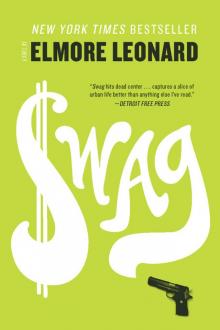

Mr Majestyk Swag

Swag Road Dogs

Road Dogs La Brava

La Brava The Hot Kid

The Hot Kid Valdez Is Coming: A Novel

Valdez Is Coming: A Novel Be Cool

Be Cool The Law at Randado

The Law at Randado The Bounty Hunters

The Bounty Hunters When the Women Come Out to Dance

When the Women Come Out to Dance 310 to Yuma and Other Stories (1953)

310 to Yuma and Other Stories (1953) Tishomingo Blues

Tishomingo Blues Cat Chaser

Cat Chaser Pagan Babies

Pagan Babies Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #1

Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #1 52 Pickup

52 Pickup Stick

Stick The Moonshine War

The Moonshine War Valdez Is Coming

Valdez Is Coming City Primeval

City Primeval Rum Punch

Rum Punch Out of Sight

Out of Sight Naked Came the Manatee (1996)

Naked Came the Manatee (1996) Killshot

Killshot Cuba Libre

Cuba Libre Forty Lashes Less One

Forty Lashes Less One The Complete Western Stories of Elmore Leonard

The Complete Western Stories of Elmore Leonard Pronto

Pronto Split Images

Split Images Last Stand at Saber River

Last Stand at Saber River The Switch

The Switch Three-Ten to Yuma and Other Stories

Three-Ten to Yuma and Other Stories Bandits

Bandits Comfort to the Enemy and Other Carl Webster Stories

Comfort to the Enemy and Other Carl Webster Stories Hombre

Hombre Trail of the Apache and Other Stories

Trail of the Apache and Other Stories LaBrava

LaBrava Gold Coast

Gold Coast Jackie Brown

Jackie Brown Escape From Five Shadows

Escape From Five Shadows Karen Makes out (1996)

Karen Makes out (1996) Up in Honey's Room

Up in Honey's Room How Carlos Webster Changed His Name to Carl and Became a Famous Oklahoma Lawman (2003)

How Carlos Webster Changed His Name to Carl and Became a Famous Oklahoma Lawman (2003) Mr. Paradise

Mr. Paradise The Hunted

The Hunted Freaky Deaky

Freaky Deaky Louly and Pretty Boy (Ss)

Louly and Pretty Boy (Ss) Glitz

Glitz A Coyote's in the House

A Coyote's in the House The Big Bounce jr-1

The Big Bounce jr-1 Up in Honey's Room cw-2

Up in Honey's Room cw-2 Unknown Man #89 jr-3

Unknown Man #89 jr-3 Get Shorty: A Novel cp-1

Get Shorty: A Novel cp-1 Gunsights

Gunsights Riding the Rap rg-2

Riding the Rap rg-2