- Home

- Elmore Leonard

Touch

Touch Read online

Touch (1987)

Leonard, Elmore

Unknown publisher (2011)

* * *

Touch

Elmore Leonard

*

A Michigan woman was blind and now she can see, after being touched by a young man who calls himself Juvenal. An evangelist and a wacko fundamentalist see dollar signs in this magic kid but Juvenal's got a trick or two up his own sleeve.

Chapter 1

FRANK SINATRA, JR., was saying, "I don't have to take this," getting up out of the guest chair, walking out. Howard Hart was grinning at him with his capped teeth.

Virginia was saying, "What's Frank Sinatra, Jr., doing? What's Howard Hart doing?"

Elwin sidearmed an empty Early Times bottle at the TV set, shattering the sixteen-inch screen, wiping out Howard Hart's grin and Frank Sinatra, Jr., going out the door. Elwin took down the presidential plates from the rail over the couch--Eisenhower, Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson and Lady Bird, Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford, all the portraits done in color--and sailed the plates one at a time at the piano, trying to skim off the silver-framed photograph of Virginia seated at the console of the Mighty Hammond organ. He missed five out of five but destroyed each of the plates against the wall back of the piano. The Early Times bottle was still good, so he smashed the photograph with that, looked around for something else, and threw the bottle end over end, like a tomahawk, exploding the big picture window for the high ultimate in glass-shattering noise.

Then he grabbed Virginia, the real Virginia--thirty pounds heavier than the smiling organist in the photograph--and as she pushed and clawed at him, trying to get loose, he threw a wild punch that grazed her head and set her screaming. Finally he was able to connect with a good one, belting her square in the face, grazing that long, skinny nose, hitting her hard enough that he hurt his hand and had to go out in the kitchen and run water on it.

When Bill Hill arrived Elwin let him in and went back through the living room to the kitchen, saying only, "She called you, huh? When she do that?" Elwin didn't care if he got an answer. He reached up to a top cupboard shelf and pulled a fifth of Jim Beam from behind the garden-fresh canned peas and cream-style corn.

Bill Hill had on his good light blue summer suit and a burgundy sport shirt with the collar open to show the heavy gold chain and medallion that was inscribed Thank you, Jesus. He had his dark hair swirled down over his forehead and sprayed hard, ready to go out for the evening, almost out the door when Virginia called. She was on the sofa now sobbing into a little satin pillow. He bent over her and said, "Here, let me see," gently taking the pillow from her face. The dark hollows of her eyes were wet, her rouge smeared and streaked, one side of her face swollen as though she had an abscessed tooth. The skin was scraped, beginning to show a bruise, but it wasn't cut or bleeding.

"What'd he hit you with, his fist?"

Virginia nodded, trying to raise the pillow again to her face. The satin material was probably cool and it was a place to hide. Bill Hill held onto the pillow, wanting her to look up at him.

"How long's he been drinking? All day?"

"All day, all yesterday." Virginia was trying to talk without moving her mouth. "I called the Center, it was about an hour ago, but nobody came. So I called you."

"I'll get you a wet cloth, okay? You're gonna be all right, Ginny. Then I'll have a talk with him."

"He never was this bad, all the other times."

"Well, they get worse," Bill Hill said, "from what I understand."

It was hot and close in the house and smelled of stale cigarette smoke, though the attic fan was going, sounding like an airplane in the upstairs hall. Elwin had a hip pressed against the sink, using a butcher knife on the Jim Beam seal. His shirt was messy, sweat-stained. His old-timey-looking slick hair hung down on both sides of his face from the part that showed white scalp and was always straight as a ruler no matter how drunk he got.

Bill Hill said, "You're a beauty. You know it?"

"I'm glad you come over to give me some of your mouth," Elwin said. "That goddamn woman, I got her shut up for a while, now I got you starting on me. Why don't you just get the hell out of here. I didn't invite you, I know goddamn well." He got the top off and poured half a jelly glass full of Jim Beam and added a splash of Seven-Up from a bottle on the counter. The sink was full of dishes and an empty milk carton. Elwin said, "You want a drink, help yourself."

"I want to know what's wrong with you," Bill Hill said, "beating up on Ginny like that. You realize what you did?"

"I realize I shut her goddamn mouth. I warned her," Elwin said. "I told her, Jesus, shut your mouth for a while, give us some peace. She kept right on." Elwin's voice rose, mimicking, as he said, " 'What're you doing, you drinking again? Getting drunk, aren't you, sucking on your whiskey bottle.' I said I'm having a couple for my goddamn nerves to lie still."

"For a couple of days," Bill Hill said. "But I guess you know what you're doing, don't you?"

"I got her shut up," Elwin said. "How many times I said, Shut up! She kept right on, yak yak yak, her mouth working like it'd never stop. Yak yak yak yak, Jesus."

"Well, you stopped her," Bill Hill said. "You gonna take her to the hospital or you want me to?"

"Hospital, shit, there's nothing wrong with her. I give her a little shove."

"Well, what if she's got a concussion of the brain," Bill Hill said, "you ever consider that? You want to come out and take a look at your wife you got up the courage to belt in the face with your fist. You're pretty brave, Elwin, I'll say that for you."

"You won't be saying nothing you keep it up," Elwin said, "you'll be spitting your teeth."

"Okay, you're tough, Elwin, and I'm scared," Bill Hill said. "But you want to talk to me a minute? Try to explain to me what happened? See, maybe I'm dumb or something. I don't understand a man taking a punch at his wife and tearing up his living room. You remember doing all that?"

"I'll tell you what the hell happened," Elwin said, "feeling that goddamn woman watching me, following me around--"

"Now wait a minute," Bill Hill said, "you're watching yourself is who's watching anybody and you know it. That's called having a guilty conscience. You hide those bottles you're hiding them from yourself."

"Bullshit, you think she can't find them? She feels all over this goddamn house, buddy, and she finds them."

"All right, you know what I'm saying," Bill Hill said. "You try not to drink for a while, you go to meetings and you get along pretty good, don't you? Then you give in, and you know what happens every time. You smash up your car. You run clear through your garage wall out the back. You start punching people--hitting guys, that's bad enough. Now you're punching your poor, defenseless wife--"

"Poor, defenseless shit--"

"Listen to me, all right? Will you just listen a minute?"

"Poor, defenseless mouth going all day long."

"Elwin, what happens every time? You smash something, don't you? Or somebody. And you end up in jail or back in the Rehabilitation Center. Is that the way you want to live?"

"I got a good idea," Elwin said.

"Okay, tell me what it is." Bill Hill looked up at him calmly. Elwin was several inches taller than Bill Hill's five nine and with big, hard bones and big, gnarled hands that looked like tree roots, working man's hands.

"Why don't you get out of here," Elwin said, "before I heave you right through the screen door. You believe I can't do it?"

"No, I believe you can," Bill Hill said, "but instead of that, why don't we see if we can get Ginny fixed up a little. What do you say?" He took a dish towel that was fairly clean and ran it under cold water and wrung it out and folded the cloth, trying not to get his suit wet or mussed up, while Elwin told him again how the woman never shut up from the time she got ou

t of bed in the morning to the time she crawled back in at night and lay there bitching in the dark, all day while he'd be trying to do some work around the house or else reading the want ads in both Detroit papers and the Oakland County Press, but was there any construction work? Shit no, cause they was letting the niggers in the union and giving them all the jobs. Then Elwin dropped his drink on the floor and had to make a new one.

Virginia looked worn out and in pain, a poor, battered wife of a laid-off construction worker. Bill Hill got her stretched out on the sofa with a pile of little pillows beneath her head. She'd moan something as he wiped off her face. He'd say, "What?" Then finally realized she was just making sounds, down in there being miserable.

He went out to the kitchen to rinse the dishcloth and told Elwin why didn't he, instead of standing there getting shit-face drunker than he already was, why didn't he straighten up the mess in the kitchen.

That was a big mistake.

Elwin said okay, he'd straighten up the mess, and began taking dishes out of the sink and dropping them on the floor, saying to Bill Hill how's that? Was that straight enough for him?

Bill Hill went back to the living room and laid the cool, damp cloth over Virginia's eyes, hearing Elwin dropping dishes and the dishes smashing on the floor. Bill Hill had a date and was going to a disco. He was thinking, Shit, he might never make it and the girl would get mad and pout sitting home with her hair done and her perfume on.

The young guy in jeans and a striped T-shirt and sneakers opened the aluminum screen door and walked in. Standing there with his fingers wedged in his pants pockets, he said, "This is the Worrels', isn't it?" Then seemed to smile a little as he saw Elwin in the kitchen dropping dishes. He said, "Yeah, I think I recognize somebody." He looked at Bill Hill and then at Virginia on the sofa. "What happened?"

"You a friend of the Worrels?" Bill Hill was guarded. He didn't know who this young guy was. But maybe the young guy had seen this show before and that's why he wasn't surprised or seemed disturbed.

"I know Elwin a little bit," the young guy said. "From when he was at Sacred Heart. They just called me to see if I could stop by, maybe talk to him. I'm Juvenal." He was looking at Virginia again, frowning a little now. "Is she all right?"

"Oh, you're from the Center," Bill Hill said. "Good. You're just the man we need." Though the young guy--Juvenal?--didn't look anything like an AA house caller, a man who'd been there and back and could understand what the drunk was going through. This one looked like a college student dressed for a picnic. No, older than that. But skinny, immature-looking, light-brown hair down over his forehead, cut sort of short. He looked like a nice, well-behaved boy that mothers of young girls would love to see come to the house.

"You said your name's . . . Juvenal?"

"That's right." The young guy raised his voice and said, "Elwin, what're you doing?"

"He's breaking dishes," Bill Hill said. What was the young guy smiling about? No, he wasn't smiling. But he seemed to be smiling, his expression relaxed, as though nothing at all was on his mind. He certainly didn't look like a drunk. He hardly looked old enough even to get a drink. Bill Hill bet, though, he was about thirty.

Elwin was hollering now, swearing goddamn it he'd get the goddamn kitchen straightened, reaching up to the cupboard to get more dishes. The young guy, Juvenal, walked past Bill Hill out of the living room to the kitchen. Bill Hill heard Elwin's voice again, then nothing. Silence. He could see the young guy saying something to Elwin, but couldn't hear him. Elwin seemed to be listening, nodding, the young guy talking with his hands in his pockets.

Bill Hill said, "Christ Almighty."

Maybe the young guy did know what he was doing. Bill Hill walked over to the kitchen doorway to see Elwin getting a broom and dustpan out of the closet. The young guy, Juvenal, was picking up Elwin's drink.

Now he'll pour it out, Bill Hill thought. Jesus, help us. And Elwin'll go berserk again.

But the young guy didn't pour it out. He took a good sip of the Jim Beam drink and put it down on the yellow tile counter again.

What the hell kind of an AA caller was he anyway? The young guy came toward Bill Hill but was looking past him into the living room.

"Is she all right?"

"I think so. He belted her a good one, but I don't believe he busted anything."

Now Elwin was leaning on his broom looking at Bill Hill. "All done," he said. "You gonna stand there with your finger up your ass or you gonna help me?"

Bill Hill said, tired, "Yeah, I'll help you." He started past the young guy.

"What's the matter with her?"

He was staring at Virginia on the sofa with the dishcloth folded over her eyes.

"He punched her in the face," Bill Hill said. "She's got a big bruise, so I put a cold cloth on it."

"No, I mean what else's wrong with her?" the young guy said. "Something is, isn't it?"

"Oh," Bill Hill said. "Well, yeah, she's blind."

"All her life?"

"Ever since I've known her." Bill Hill glanced over at the sofa, keeping his voice low. "Ginny got hit in the head in a car wreck about fifteen years ago. Yeah, in Sixty-two. It left her blind."

Juvenal moved past him.

Bill Hill watched him go over and look down at Virginia, his hands in his pockets, then the hands coming out of the pockets as he sat down on the edge of the sofa, his back to the kitchen. Bill Hill saw him raise the dishcloth from Virginia's eyes.

Elwin said, "You want to know something? Virginia's mother give us these dishes when we got married and all that time, Christ, twenty-one years, I hated those goddamn dishes. Got little rosebuds on 'em--"

Bill Hill turned to Elwin and took the dishpan from the table.

"--but I never said nothing. All that time, you'd get down through your mashed potatoes and wipe up your gravy? There'd be these little goddamn rosebuds looking at you. The only thing I said once, I said it looked like a goddamn little girl's tea set and Virginia got sore and started to cry. Shit, anything I didn't like, if I said it? She'd start to cry, like I was blaming her for it. I'd say goddamn it, what I think has got nothing to do with you, does it? She'll do it again. She'll reach up in the cupboard and say where's all my good dishes for heaven sake? And I'll tell her I got rid of those goddamn rosebud dishes finally, I finally got the nerve to get rid of them." Still rough talking, but his tone had changed, the meanness gone. Bill Hill noticed it.

He said, "Well, you might've bought some others first, since you're out of work and you got all this extra cash laying around."

"He come in here and says what're you doing. Juvie did," Elwin said. "I told him I always hated those goddamn rosebud dishes and I'm busting them. And he said, you know what he said? He said, 'I don't blame you.' "

Bill Hill wanted to ask about the young guy, who he was. Was he AA or not? Did he work at the Center in rehabilitation? If he did, how come he took a drink?

But Virginia began to call. She said, "Elwin?" In a sharp little surprised tone. She said, "Elwin, my God. Come here."

Both of them went into the living room, Elwin still holding the broom.

Virginia was sitting up, holding the dishcloth in her lap and turning her head carefully, as though she had a stiff neck, turning to the piano and then slowly turning her head toward the kitchen doorway. She looked different.

Elwin said, "Jesus, I cut her, didn't I?"

Bill Hill said, almost under his breath, "No, you didn't. I'm sure you didn't." That was the whole thing, why he was more surprised than Elwin; because he had wiped off her face and looked at the bruise closely. Except for a scrape and the swelling there hadn't been a mark on her. But now there was a smear of blood on her face, over her forehead and cheeks. At least it looked like blood.

Bill Hill said, "Ginny, you all right?"

Something scared him and kept him from moving.

He noticed now that the young guy, Juvenal, wasn't in the room. Though he might've gone up to the bathroom. Or he might'

ve left. But that would be strange, coming here on a call and then leaving without saying anything.

Elwin said, "Virginia, I got to tell you something."

She said, "Tell me."

"Well, later on," Elwin said.

Bill Hill kept staring at her. What was it? She moved on the sofa, turning now to look directly at them. She looked worse than before. Battered, swollen, and now bloody. She seemed about to cry. But--what it was--she didn't seem miserable now. She was calm. She was looking at them out of dark shadows and her eyes were alive.

"What're you doing with a broom?" Virginia said and seemed to smile, waiting.

Bill Hill didn't take his eyes from her. He heard Elwin say, "Jesus Christ," reverently, like a prayer. Neither of them moved.

"I can see," Virginia said. "I can see both of you plain as day."

Chapter 2

BILL HILL had to ring the doorbell to get into the Sacred Heart Rehabilitation Center, then had to explain why he wanted to see Father Quinn--about his good friend Elwin Worrel who'd been here and was drinking again--then had to wait while they looked for Quinn.

It was not like a hospital. The four-story building on the ghetto edge of downtown Detroit had once been a branch of the YWCA for black women, before integration, and that's what he decided it looked like, a YWCA.

He watched a man in pajamas, with slicked-back, wet-looking hair and round shoulders, go up to the reception desk where a young guy in a T-shirt and a good-looking black girl were on duty. The man in pajamas, feeling his jaw with his fingers, asked for some after-shave lotion. The young guy handed him a bottle of Skin Bracer. The man stuck his chin out, rubbed the Skin Bracer over his face and neck, and walked away, leaving the bottle on the counter. The young guy screwed the cap back on and put the bottle away somewhere.

Bill Hill strolled over and leaned against the counter. He said to the good-looking black girl, "Is Juvenal around?"

She said, "Juvenal?" a little surprised. The young guy in the T-shirt said, "I don't think he's here." He turned to look at a schedule of names and dates tacked to the wall above the switchboard. "No, Juvie's off today."

Charlie Martz and Other Stories: The Unpublished Stories

Charlie Martz and Other Stories: The Unpublished Stories Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #2

Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #2 Fire in the Hole

Fire in the Hole Tishomingo Blues (2002)

Tishomingo Blues (2002) Djibouti

Djibouti When the Women Come Out to Dance: Stories

When the Women Come Out to Dance: Stories Riding the Rap

Riding the Rap Moment of Vengeance and Other Stories

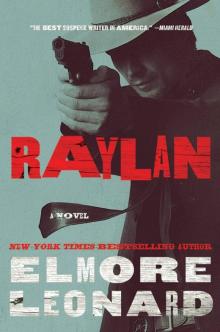

Moment of Vengeance and Other Stories Raylan

Raylan Touch

Touch Mr Majestyk

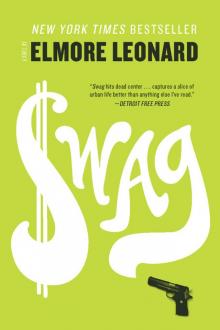

Mr Majestyk Swag

Swag Road Dogs

Road Dogs La Brava

La Brava The Hot Kid

The Hot Kid Valdez Is Coming: A Novel

Valdez Is Coming: A Novel Be Cool

Be Cool The Law at Randado

The Law at Randado The Bounty Hunters

The Bounty Hunters When the Women Come Out to Dance

When the Women Come Out to Dance 310 to Yuma and Other Stories (1953)

310 to Yuma and Other Stories (1953) Tishomingo Blues

Tishomingo Blues Cat Chaser

Cat Chaser Pagan Babies

Pagan Babies Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #1

Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #1 52 Pickup

52 Pickup Stick

Stick The Moonshine War

The Moonshine War Valdez Is Coming

Valdez Is Coming City Primeval

City Primeval Rum Punch

Rum Punch Out of Sight

Out of Sight Naked Came the Manatee (1996)

Naked Came the Manatee (1996) Killshot

Killshot Cuba Libre

Cuba Libre Forty Lashes Less One

Forty Lashes Less One The Complete Western Stories of Elmore Leonard

The Complete Western Stories of Elmore Leonard Pronto

Pronto Split Images

Split Images Last Stand at Saber River

Last Stand at Saber River The Switch

The Switch Three-Ten to Yuma and Other Stories

Three-Ten to Yuma and Other Stories Bandits

Bandits Comfort to the Enemy and Other Carl Webster Stories

Comfort to the Enemy and Other Carl Webster Stories Hombre

Hombre Trail of the Apache and Other Stories

Trail of the Apache and Other Stories LaBrava

LaBrava Gold Coast

Gold Coast Jackie Brown

Jackie Brown Escape From Five Shadows

Escape From Five Shadows Karen Makes out (1996)

Karen Makes out (1996) Up in Honey's Room

Up in Honey's Room How Carlos Webster Changed His Name to Carl and Became a Famous Oklahoma Lawman (2003)

How Carlos Webster Changed His Name to Carl and Became a Famous Oklahoma Lawman (2003) Mr. Paradise

Mr. Paradise The Hunted

The Hunted Freaky Deaky

Freaky Deaky Louly and Pretty Boy (Ss)

Louly and Pretty Boy (Ss) Glitz

Glitz A Coyote's in the House

A Coyote's in the House The Big Bounce jr-1

The Big Bounce jr-1 Up in Honey's Room cw-2

Up in Honey's Room cw-2 Unknown Man #89 jr-3

Unknown Man #89 jr-3 Get Shorty: A Novel cp-1

Get Shorty: A Novel cp-1 Gunsights

Gunsights Riding the Rap rg-2

Riding the Rap rg-2