- Home

- Elmore Leonard

Valdez Is Coming: A Novel Page 4

Valdez Is Coming: A Novel Read online

Page 4

Now. “Mr. Tanner, do you remember me? Bob Valdez, from the pasture today.”

Tanner held the cigar in front of him. He was in his shirtsleeves and vest and without the dark hat that had hidden his eyes, his hair slanting down across his forehead, the skin pale-looking in the firelight. He seemed thinner now and smaller, but his expression was the same, the tell-nothing expression and the mouth that looked as if it had never smiled.

“What do you want?”

“I just wanted to talk to you for a minute.”

“Say it.”

“Well, it’s about the man today.”

“What man?”

“The one that was killed. You know he had a wife with him.” Valdez waited.

“Say what you want and get out of here.”

“Well, we were talking—Mr. Beaudry and Mr. Malson. You know who I mean?”

“You don’t have much time left,” Mr. Tanner said.

“We were saying maybe we should give something to the woman now that she doesn’t have a husband.”

“They sent you out here?”

“No, I thought of it. I thought if we all put in to give her some money”—he hesitated—“about five hundred dollars.”

Mr. Tanner had not moved his gaze from Valdez. “You come out here to tell me that?”

“Well, we were talking about it and Mr. Beaudry said why don’t I see you about it.”

“You want me to pay money,” Mr. Tanner said, “to that red nigger he was holed up with?”

“You said it wasn’t the right man——”

“What’s that got to do with it?”

“It was an accident, not the woman’s fault, and she doesn’t have anything now. And she’s got that child she’s going to have. Did you see that?”

Mr. Tanner looked at his segundo. He said, “Get rid of him,” and started to turn away.

“Wait a minute!”

Valdez watched him half turn to look at him again.

“What did you say?”

“I mean if you could take time to listen a minute so I can explain it.” The hard-working, respectful Bob Valdez speaking again, smiling a little.

“Your minute’s up, boy.” He glanced at his segundo again. “Teach him something.” He turned and was gone.

Valdez called out, “Mr. Tanner——”

“He don’t hear you so good,” the segundo said. “It’s too loud out here.” He drew the .44 on his right leg, cocked it and fired as he brought it up, and with the explosion the adobe chipped next to Bob Valdez’s face.

“All this shooting,” the segundo said. “Man, he can’t hear anything.” He fired again and the adobe chipped close to the other side of Valdez’s face. “You see how easy it would be?” the segundo said.

The Mexican rider who had brought him in said, “Let me have one,” his revolver already drawn. “Where do you want it?”

“By the right hand,” the segundo said.

Valdez was looking at the Mexican rider. He saw the revolver lift as the man pulled the trigger and saw the muzzle flash with the heavy solid noise and heard the bullet strike close to his side.

“Too high,” the segundo said.

Now those who were sitting and lounging by the fires rose and drew their revolvers, looking at the segundo and waiting their turn. One of them, an American, said, “I know where I’m going to shoot the son of a bitch.” One of them laughed and another one said, “See if you can shoot his meat off.” And another one said, “It would fix this squaw-lover good.”

Bob Valdez did not want to move. He wanted to run and he could feel the sweat on his face, but he couldn’t move a hand or an elbow or turn his head. He had to stay rigid without appearing to be rigid. He edged his left foot back and the heel of his boot touched the wall close behind him. He did that much, touching something solid and holding on, as the men faced him across the fires, five or six strides away from him, close enough to put the bullets where they wanted to put them—if all of the men knew how to shoot and if they hadn’t had too much mescal or tequila since coming to the station. Valdez held on and now kept his eyes on the segundo for a place to keep them, a point to fix on while they played their game with him.

The first few men fired in turn, calling their shots; but now the rest of them were anxious and couldn’t wait and they began firing as they decided where to shoot, raising the revolvers in front of them but not seeming to aim, pulling the triggers in the noise and smoke and leaning in to see where their bullets struck. Valdez felt his hat move and felt powder dust from the adobe brick in his eyes and in his nose and felt chips of adobe sting his face and hands and felt a bullet plow into the wall between his knees and a voice say, “A little higher you get him good.” Another voice, “Move up a inch at a time and watch him poop his drawers.”

He kept his eyes on the segundo in the Sonora straw, not telling the segundo anything with his gaze, looking at him as he would look at any man, if he wanted to look at a man, or as he would look at a horse or a dog or a steer or an object that was something to look at. But as he saw the segundo staring back at him he realized that he was telling the segundo something after all. Good. He had nothing to lose and now was aware of himself staring at the segundo.

What can you do? he was saying to the segundo. You can kill me. Or one of them can kill me not meaning to. But what else can you do to me? You want me to get down on my knees? You don’t have enough bullets, man, and you know it. So what can you do to me? Tell me.

The segundo raised his hand and called out, “Enough!” in English and in Spanish and in English again. He walked between the fires to Bob Valdez and said, “You ride out now.”

Bob Valdez took his hat off, adjusting it, loosening it on his head. He didn’t touch his face to wipe away the brick dust and sweat or look at his hands, though he felt blood on his knuckles and running down between his fingers.

He said, “If you’re through,” and walked away from the segundo. He mounted the company horse and rode out the gate, the segundo watching him until he was into the darkness and only a faint sound of him remained.

The men were talking and reloading, spinning the cylinders of their revolvers, sitting by the fires to rest and to tell where they had put their bullets. The segundo walked away from them out into the yard, listening to the silence. After a few minutes he went under the ramada to enter the adobe.

The station man, Gregorio Sanza, behind the plank bar and beneath the smoking oil lamp, raised a mescal bottle to the segundo, pale yellow in the light; but the segundo shook his head; he walked over to the long table where Tanner was sitting with the woman. She was sipping a tin cup of coffee.

The woman had gone into a sleeping room shortly after they had arrived in the buggy and had remained there until now. The segundo saw she was still dressed and he wondered what she had been doing in the room. In the months she had been with them—since Tanner had brought her over from Fort Huachuca—the segundo could count the times he had spoken to her on his hands. She seldom asked for anything; she never gave the servants orders as the woman of the house was supposed to do. Still, she had the look of a woman who would be obeyed. She did not seem afraid or uneasy; she looked into your eyes when she spoke to you; she spoke loud enough yet quietly. But something was going on in her head beneath the long gold-brown hair that hung past her shoulders. She was a difficult woman to understand because she did not give herself away. Except that she smiled only a little, and he had never seen her laugh. Maybe she laughed when she was alone with Señor Tanner.

If she was my woman, the segundo was thinking, I could make her laugh and scream and bite.

He said to Tanner, “The man’s gone.”

“How did he behave?”

“He stood up.”

Tanner drew on the fresh cigar he was smoking. “He did, uh?”

“As well as a man can do it.”

“He didn’t beg?”

The segundo shook his head. “He said nothing.”

&nb

sp; “He shot the nigger square,” Tanner said. “He did that well. But outside, I thought he would crawl.”

The segundo shook his head again. “No crawling or begging.”

“All right, tell that man to close his bar and go to bed.”

The segundo nodded and moved off.

Tanner waited until the segundo had stopped at the bar and had gone outside. “Why don’t you go to bed, too,” he said to the woman.

“I will in a minute.” She kept her finger in the handle of the coffee cup.

“Go in and pretty yourself up,” he said then. “I’ll take a turn around the yard and be in directly.”

“What did the man do?”

“He wasted my time.”

“So they put him against the wall?”

“It was the way he spoke to me,” Tanner said. “I can’t have that in front of them.” He sat close to her, staring into her face, at the gray-green eyes and the soft hair close to her cheek. His hand came up to finger the end strands of her hair. Quietly, he said, “Gay, go on in the room.”

“I’ll finish my coffee.”

“No, right now would be better. I’ll be there in a minute.”

She waited until he was out of the door before rising and going into the sleeping room. In the dim lamplight she began to undress, stepping out of her dress and dropping it on the bed next to her nightgown. The light blue one. Thin and limp and patched beneath one arm. There had been a light blue one and a light green one and a pink one and a yellow one, all with the white-scrolled monogram GBE she had embroidered on the bodice when she was nineteen years old and living in Prescott, a girl about to be married. The girl, Gay Byrnes, had brought the nightgowns and her dresses and linens to Fort Huachuca to become the bride of James C. Erin. During five and a half years as his wife she discarded the nightgowns one by one and used them as dust rags. When her husband was killed six months ago, and she left Huachuca with Frank Tanner, she had only the light blue one left.

Gay Erin slipped the nightgown over her head, brushed her hair and got into the narrow double bed, pulling the blanket up over her shoulder as she rolled to her side, her back to the low-burning lamp.

When Tanner came in and began to undress, she remained with her back to him. She could see him from times before: removing his boots, his shirt and trousers, standing in his long cotton underwear as he unfastened the buttons. He would stand naked scratching his stomach and chest, then go to the wall hook and take his revolver from the holster, making sure the hammer was on an empty chamber as he moved toward the bed.

She felt the mattress yield beneath his weight. The gun would be at his side, under the blanket and next to his hip. He would lie still for a few moments, then roll toward her and put his hand on her shoulder.

“What have you got the nightgown on for?”

“I’m cold.”

“Well now, what do you think I’m for?”

“Tell me,” Gay Erin said.

“I’ll show you.”

“As a lover or a husband?”

Tanner groaned. “Jesus Christ, are you going to start that?”

“Six months ago you said we’d be married in a few weeks.”

“Most people probably think we already are. What’s the difference?”

She started to get up, to throw back the blanket, and his hand tightened on her arm.

“I said we’d be married, we will.”

“When?”

“Well not right now, all right?” His hand stroked her arm beneath the flannel. “Come on, take this thing off.”

She lay without moving, her eyes open in the darkness, letting her hesitation stretch into silence, a long moment, before she sat up slowly and worked the nightgown out from beneath her. She pulled it over her head, turning to him.

3

Inez was fat and took her time coming over from the stove with the coffeepot. Filling the china cup in front of Bob Valdez and then her own, Inez said, “She left early. It must have been before daybreak.”

“You hear her?”

“No, maybe one of the girls did. I can ask.”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“I heard what you’re doing,” Inez said.

“Well, I’m not doing very good. I wanted to tell the woman maybe it would take me a little longer.”

“You’re crazy.”

“Listen, I’m tired,” Valdez said. “I’m not going to argue with you, all right?”

“Go upstairs.”

“I said I’m tired.”

“So are the girls. I mean take a room and go to sleep.”

“I have a run to St. David this afternoon and don’t come back till the morning.”

“Tell them you’re sick.”

“No, they don’t have anybody.”

“That Davis was in here last night. I threw him out.”

“You can do it,” Valdez said.

“He was in no condition. Only talk. I don’t need talk,” Inez said. She made a noise sipping her coffee and watched Valdez shape a cigarette. He handed it to her and made another one and lit them with a kitchen match.

“Now what do you do, forget the whole thing?”

“I don’t know.” He rubbed a gnarled brown hand over his hair, pulling it down on his forehead. “I think maybe talk to this Mr. Tanner again.”

“You’re crazy.”

“I didn’t explain it to him right. The part that it’s like a court where you get money for something done to you. Not like a court, but, you know.”

“You’re still crazy. He won’t listen to you. Nobody will.”

“But if he does, the others will, uh?” Valdez sipped his coffee.

“Put a gun in his back if you can get close to him,” Inez said. “That’s the only way.”

“No guns.”

“The little shotgun.”

Valdez nodded, thinking about it. “That would be good, wouldn’t it?”

“Boom!” Inez laughed out and the sound of her voice filled the kitchen.

Valdez smiled. “Has he ever been in here?”

“They say he’s got a woman. Maybe he beats her or does strange things to her.”

“He’s never been here, but you don’t like him,” Valdez said. “Why?”

“My book.”

“Ah, your book. I forgot about it.”

“You’re in it.”

“Sure, I remember now.”

Inez called out, “Polly!” and waited a moment and called again.

A dark-haired girl in a robe came through the door from the front room. She smiled at Bob Valdez, holding the robe together in front of her. “Early bird,” she said.

“No early bird. Get me the book,” Inez said.

“Which, the black one?”

“No, the one before,” Inez said. “The green one.”

Valdez shook his head. “Black ones and green ones. How many do you have?”

“They go back about twelve years. To your time.”

“Like I’m an old man now.”

“Sometime you act it.”

The girl came into the kitchen again with the scrapbook under her arm. “The green one,” she said, winking at Bob Valdez and handing it to Inez, who pushed her coffee cup out of the way to open the book on the table. Inez sat at the end of the kitchen table with Polly standing behind her now, looking over her shoulder. Sitting to the side, Valdez lowered and cocked his head to look at the newspaper clippings and photographs mounted in the book.

“He seems familiar,” Valdez said.

Inez looked at him. “I hope so. It’s Rutherford Hayes.”

“Well, that was twelve, fourteen years ago,” Valdez said. He looked up as Polly laughed. She was leaning over Inez and the top of her robe hung partly open.

There were photographs of local businessmen, territorial officials and national figures, including two presidents, Rutherford Hayes and Chester A. Arthur, Profirio Díaz and Carmelita at Niagara Falls, and the Prince of Wales on his visit to Was

hington.

“Have they been to your place?” Valdez asked.

“No, but if they come I want to recognize them.” Inez turned a page. “Earl Beaudry, on his appointment as land agent.” Inez moved to the next page, her finger tracing down the column of newspaper clippings.

“Here it is,” she said. “The first mention of him. August 13, 1881—Frank Tanner and a Carlisle Baylor were convicted of cattle theft and sent to Yuma Penitentiary.”

Valdez seemed as pleased as he was surprised. “He’s been to prison.”

“For a few years, I think,” Inez said. “It doesn’t say how long. He was stealing cattle and driving them across the border. There’s more about him.” Her hand moved down the column and went to the next page. “Here, October, 1886, Frank J. Tanner, cattle broker, arraigned on a charge of murder in Contention, Arizona.”

“Cattle broker now,” Valdez said.

“The case was dismissed.”

“It’s getting better.”

Inez turned the page. “Ah, here’s the picture. You see him there?” Inez turned the book halfway toward Valdez and he leaned in, recognizing Tanner standing with a group of Army officers in front of an adobe building.

Inez read the caption. “It says he has a contract with the government to supply remounts to the Tenth United States Cavalry at Fort Huachuca.” She turned a few more pages. “I think that’s all.”

“Nothing about him now, uh?”

“There’s something else sticks in my mind about Huachuca,” Inez said, “but I don’t see it. Unless—sure, it would be in the other book.” She sat back in her chair looking up over her shoulder. “Polly?”

Valdez watched the girl straighten and draw the robe together.

“Should I take this one?” the girl asked.

Inez was turning pages again. “No, I want to show Bob something.”

“What have you got now?” he asked her.

Coming to a page, she pressed it flat and turned the book to him. “You remember?”

Valdez smiled a little. “That one.”

It was a photograph of Bob Valdez taken at Fort Apache, Arizona, September 7, 1884: Bob Valdez standing among small trees and cactus plants the photographer had placed in his studio shed as a background: Bob Valdez with a Sharps .50 cradled in one arm and a long-barreled Walker Colt on his leg. He was wearing a hat, with a bandana beneath it that covered half of his forehead, a belt of cartridges for the Sharps, and knee-length Apache moccasins. The caption beneath the picture described Roberto Valdez as chief of scouts with Major General George Crook, Department of Arizona, during his expedition into Sonora against hostile Apaches.

Charlie Martz and Other Stories: The Unpublished Stories

Charlie Martz and Other Stories: The Unpublished Stories Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #2

Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #2 Fire in the Hole

Fire in the Hole Tishomingo Blues (2002)

Tishomingo Blues (2002) Djibouti

Djibouti When the Women Come Out to Dance: Stories

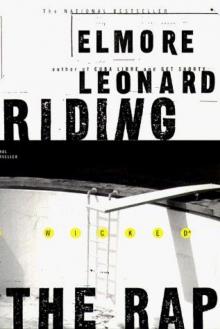

When the Women Come Out to Dance: Stories Riding the Rap

Riding the Rap Moment of Vengeance and Other Stories

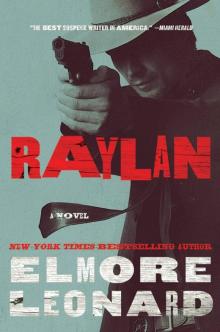

Moment of Vengeance and Other Stories Raylan

Raylan Touch

Touch Mr Majestyk

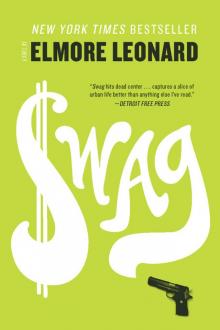

Mr Majestyk Swag

Swag Road Dogs

Road Dogs La Brava

La Brava The Hot Kid

The Hot Kid Valdez Is Coming: A Novel

Valdez Is Coming: A Novel Be Cool

Be Cool The Law at Randado

The Law at Randado The Bounty Hunters

The Bounty Hunters When the Women Come Out to Dance

When the Women Come Out to Dance 310 to Yuma and Other Stories (1953)

310 to Yuma and Other Stories (1953) Tishomingo Blues

Tishomingo Blues Cat Chaser

Cat Chaser Pagan Babies

Pagan Babies Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #1

Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #1 52 Pickup

52 Pickup Stick

Stick The Moonshine War

The Moonshine War Valdez Is Coming

Valdez Is Coming City Primeval

City Primeval Rum Punch

Rum Punch Out of Sight

Out of Sight Naked Came the Manatee (1996)

Naked Came the Manatee (1996) Killshot

Killshot Cuba Libre

Cuba Libre Forty Lashes Less One

Forty Lashes Less One The Complete Western Stories of Elmore Leonard

The Complete Western Stories of Elmore Leonard Pronto

Pronto Split Images

Split Images Last Stand at Saber River

Last Stand at Saber River The Switch

The Switch Three-Ten to Yuma and Other Stories

Three-Ten to Yuma and Other Stories Bandits

Bandits Comfort to the Enemy and Other Carl Webster Stories

Comfort to the Enemy and Other Carl Webster Stories Hombre

Hombre Trail of the Apache and Other Stories

Trail of the Apache and Other Stories LaBrava

LaBrava Gold Coast

Gold Coast Jackie Brown

Jackie Brown Escape From Five Shadows

Escape From Five Shadows Karen Makes out (1996)

Karen Makes out (1996) Up in Honey's Room

Up in Honey's Room How Carlos Webster Changed His Name to Carl and Became a Famous Oklahoma Lawman (2003)

How Carlos Webster Changed His Name to Carl and Became a Famous Oklahoma Lawman (2003) Mr. Paradise

Mr. Paradise The Hunted

The Hunted Freaky Deaky

Freaky Deaky Louly and Pretty Boy (Ss)

Louly and Pretty Boy (Ss) Glitz

Glitz A Coyote's in the House

A Coyote's in the House The Big Bounce jr-1

The Big Bounce jr-1 Up in Honey's Room cw-2

Up in Honey's Room cw-2 Unknown Man #89 jr-3

Unknown Man #89 jr-3 Get Shorty: A Novel cp-1

Get Shorty: A Novel cp-1 Gunsights

Gunsights Riding the Rap rg-2

Riding the Rap rg-2