- Home

- Elmore Leonard

Valdez Is Coming Page 13

Valdez Is Coming Read online

Page 13

Valdez lowered the glasses. He said, "Nineteen. You missed two of them, but that's very good." He looked at her, at her hair in the afternoon sunlight, the bandana pulled down from her face, loose around her neck now. He reached over and touched the bandana, feeling the cotton cloth between his fingers. "Put this on your head."

"The sun doesn't bother me," she said. She had not spoken since they left the arroyo.

"I'm not thinking of the sun. I'm thinking how far you can see yellow hair."

As she untied the knot behind her neck she said, "You believed I cut you loose. I didn't tell you I did."

"But you let me believe it."

"How do you know he did?"

"Because he told me. Because if someone else did it, he would think I knew who did it and he wouldn't bother to lie. I think I was dreaming of a woman giving me water," Valdez said. "So when I tried to remember what happened, I thought it was a woman."

"I didn't mean to lie to you," she said. "I was afraid."

"I can see it," Valdez said. "If you saved my life, I'm not going to shoot you. Or if you get under a blanket with me."

"I tried to explain how I felt," she said.

"Sure, you're all alone, you need somebody. Don't worry anymore. I know a place you can work, make a lot of money."

"If you think I'm lying," the woman said, "or if you think I'm a whore, there's nothing I can do about it. Think what you like."

"I've got something else to think about," Valdez said. He studied the slope through the field glasses, past Davis lying behind the rock looking up at him, to the point rider. He raised up then and said to Davis, "If you call out, I give you the first one."

He put the glasses on the point man again, three hundred yards away, and held him in focus until he was less than two hundred yards and he could see the man's face and the way the man was squinting, his gaze inching over the hillside. I don't know you, Valdez said to the man. I have nothing against you. He put down the field glasses and turned the Sharps on the point rider. He could still see the man's face, his eyes looking over the slope, not knowing it was coming. You shouldn't have looked at him. Valdez thought.

Then take another one and show them something. But not Tanner. Anyone else.

Through the field glasses he picked out Tanner almost four hundred yards away and put the glasses down again and placed the front sight of the Sharps on the man next to Tanner, not having seen the man or thinking about him now as a man. He let them come a little more, three hundred and fifty yards, and squeezed the trigger. The sound of the Sharps cracked the stillness, echoing across the slope, and the man, whoever he was, dropped from the saddle. Valdez looked and fired and saw a horse go down with its rider. He fired again and dropped another horse as they wheeled and began to fall back out of range. The Sharps echoed again, but they were moving in confusion and he missed with this shot and the next one. He picked up the Winchester, getting to his knees, and slammed four shots at the point rider, chasing him down the slope, and with the fourth shot the man's horse stumbled, throwing him from the saddle. He fired the Winchester twice again, into the distance, then lowered it, the ringing aftersound of the gunfire in his ears.

"Now think about it," Valdez said to Tanner.

He would think and then he would send a few, well out of range, around behind them. Or he would have some of them try to work their way up the slope without being seen.

Or they would all come again.

As they did a few minutes later, spread out and running their horses up the slope. Valdez used the Sharps again. He hit the first man he aimed at, dumping him out of the saddle, and dropped two horses. Before they had gotten within two hundred yards they were turning and falling back. He looked for the two riders whose horses he had hit. One of them was running, limping down the hill, and the other was pinned beneath his dead animal.

"You'd better move back or work around," Valdez said to Tanner, "before you lose all your horses."

Make him believe you.

He raised the angle of the Sharps and fired. He fired again and saw a horse go down at six hundred yards. They pulled back again.

Now, Valdez thought, get out of here.

They could wait until dark, but that would be too late if Tanner was sending people around. He had to be lucky to win and he had to take chances in order to try his luck.

He could leave R. L. Davis.

But he looked at him down there with his wrists tied to his belt, and for some reason he said to himself, Keep him. Maybe you need him sometime.

He called to Davis, "Come up now. Slowly, along the brush there."

The woman sat on the ground watching him. The woman who was alone and needed someone and wanted to be held and got under the blanket. In this moment before they made their run, Valdez looked at her and said, "What do you want? Tell me."

"I want to get out of here," she said.

"Where? Where do you want to be?"

"I don't know."

"Gay Erin," Valdez said, "think about it and let me know."

Tanner and the men with him had gotten to the ridge and were looking at the ground and back down the slope to where they had been, seeing it as Valdez had seen it. Now they heard the gunfire in the distance, to the south.

They stopped and looked that way, all of them, out across the open, low-rolling country to the hills beyond.

"They caught him," one of them said.

Another one said, "How many shots?"

They listened and in the silence a man said, "I counted five, but it could've been more."

"It was more than five," the first man said. "It was all at once, like they were firing together."

"That's it," a man said. "The four of them got him in their sights and all fired at once to finish him."

The segundo was standing at the place where Valdez had positioned himself belly-down behind the rocks to fire at them. He picked up an empty brass cartridge and looked at it -- fifty-caliber big bore, from a Sharps or some kind of buffalo gun. He noticed the .44 cartridges that had been fired from the Winchester. A Sharps and a Winchester, a big eight- or ten-bore shotgun and a revolver; this man was armed and he knew how to use his guns. The segundo counted fourteen empty cartridges on the ground and tallied what the bullets had cost them: two dead on the slope, two wounded, five horses shot. Now seven dead in the grand total and, counting the men without horses, who would have to walk to Mimbreno and come back, twelve men he had wiped from the board, leaving twelve to hunt him and kill him.

He said to Mr. Tanner, "This is where he was, if you want to see how he did it."

Tanner walked over, looking at the ground and down the slope. "He had some luck," Tanner said, "but it's run out."

The segundo said nothing. Maybe the man had luck -- there was such a thing as luck -- but God in heaven, he knew how to shoot his guns. It would be something to face him, the segundo was thinking. It would be good to talk to him sometime, if this had not happened and if he met the man, to have a drink of mescal with him, or if they were together using their guns against someone else.

How would you like to have him? the segundo thought. Start over and talk to him different. He remembered the way Valdez had stood at the adobe wall as they fired at him, shooting close to his head and between his legs. He remembered the man not moving, not tightening or pleading or saying a word as he watched them fire at him. You should have known then, the segundo said to himself.

Tanner had sent four to circle around behind Valdez on the ridge and close his back door. A half hour after they heard the gunfire in the distance, one of them came back.

The man's horse was lathered with sweat, and he took his hat off to feel the evening breeze on the ridge as he told it.

"We caught them, out in the open. They had miles to go yet before they'd reach cover, and we ran them, hard," the man said. "Then we see one of the horses pull up. We know it must be him and we go right at him, getting into range to start shooting. But he goes flat on the ground, out in

the open but right flat, and doesn't give us nothing to shoot at. He opened up at about a hunnert yards, and first one boy went down and then he got the horse of this other boy. The boy run toward him and he cut him clean as he was a-running. So two of us left, we come around. We see Valdez mount up and chase off again for the hills. We decide, one of us will follow them and the other will come back here."

Tanner said, "Did you hit him?"

"No sir, he didn't look to be hit."

"You know where he went?"

"Yes sir, Stewart's out there. He's going to track them and leave a plain enough trail for us to follow."

Tanner looked at the segundo. "Is he any good?"

The segundo shrugged. "Maybe he's finding out."

They moved out, south from the ridge, across the open, rolling country. In the dusk, before the darkness settled over the hills, they came across the man's horse grazing, and a few yards farther on the man lying on his back with his arms flung out. He had been shot through the head.

Ten, the segundo thought, looking down at the man. Nine left.

"Take his guns," Tanner said. "Bring his horse along."

It was over for this day. With the darkness coming they would have to wait until morning. He took out a cigar and bit off the end. Unless they spread out and worked up into the hills tonight. Tanner lighted the cigar, staring up at the dim, shadowed slopes and the dark mass of trees above the rocks.

He said to the segundo, "Come here. I'll tell you what we're going to do."

Chapter 8

"Christ," R. L. Davis said. "I need more than this to eat." Christ, some bread and peppers and a half cup of stale water. "I didn't have nothing all day."

"Be thankful," Valdez told him.

Davis's saddle was on the ground in front of him, his hands tied to the horn. He was on his stomach and had to hunch his head down to take a bite of the pan bread he was holding. The Erin woman, next to him, held his cup for him when he wanted a sip of water. She listened to them, to their low tones in the darkness, and remained silent.

"I don't even have no blanket," R. L. Davis said. "How'm I going to keep warm?"

"You'll be sweating," Valdez said.

"Sweating, man it gets cold up here."

"Not when you're moving."

Davis looked over at him in the darkness, the flat, stiff piece of bread close to his face. "You don't even know where you're going, do you?"

"I know where I want to go," Valdez answered. "That much."

Toward the twin peaks, almost a day's ride from where they were camped now for a few hours, in the high foothills of the Santa Ritas: a dry camp with no fire, no flickering light to give them away if Tanner's men were prowling the hills. They would eat and rest and try to cover a few miles before dawn.

Ten years before, he had camped in these hills with his Apache trackers, following the White Mountain band that had struck Mimbreno and burned the church and killed three men and carried off a woman: renegades, fleeing into Mexico after jumping the reservation at San Carlos, taking what they needed along the way.

Ten years ago, but he remembered the ground well, and the way toward the twin peaks.

Valdez had worked ahead with his trackers and let the cavalry troop try to keep up with them, moving deep into the hills and climbing gradually into rock country, following the trail of the White Mountain band easily, because the band was running, not trying to cover their tracks, and because there were many of them: women and several children in addition to the fifteen or so men in the raiding party. He knew he would catch them, because he could move faster with his trackers and it was only a matter of time. They found cooking pots and jars that had been stolen and now thrown away. They found a lame horse and farther on a White Mountain woman who was sick and had been left behind. They moved on, climbing the slopes and up through the timber until they came out of the trees into a canyon: a gama grass meadow high in the mountains, with an escarpment of rock rising steeply on both sides and narrowing at the far end to a dark, climbing passage that would allow only one man at a time to enter.

The first tracker into the passage was shot from his saddle. They carried him back and dismounted in the meadow to look over the situation.

This was the reason the White Mountain band had made a run for it and had not bothered to cover their tracks. Once they made it through the defile they were safe. One of them could squat up there in the narrows and hold off every U. S. soldier on frontier station, as long as he had shells, giving his people time to run for Mexico. They studied the walls of the canyon and the possible trails around. Yes, a man could climb it maybe, if he had some goat blood in him. But getting up there didn't mean there was a way to get down the other side. On the other hand, to go all the way back down through the rocks and find a trail that led around and brought them out at the right place could take a week if they were lucky. So Valdez and his trackers sat in that meadow and smoked cigarettes and talked and let the White Mountain people run for the border. If they didn't get them this year they'd get them next year.

Valdez could see Tanner's men dismounted in the meadow, looking up at the canyon walls, studying the shadowed crevices and the cliff rose that grew along the rim, way up there against the sky. Anyone want to try it? No thank you, not today. Tanner would send some men to scout a trail that led around. But before he ever heard from them again, after a day or two in the meadow, seeing the bats flicking and screeching around the canyon's wall at night, he'd come to the end of his patience and holler up through the narrow defile, "All right, let's talk!"

That was the way Bob Valdez had pictured it taking place: leading Tanner with plenty of time and setting it up to make the deal. "Give me the money for the Lipan woman or you don't get your woman back."

He had almost forgotten the Lipan woman. He couldn't picture her face now. It wasn't a face to remember, but now the woman had no face at all. She was somewhere, sitting in a hut eating corn or atole, feeling the child inside her and not knowing this was happening outside in the night. He would say to Tanner, "You see how it is? The woman doesn't have a man, so she needs money. You have money, but you don't have a woman. All right, you pay for the man and you get your woman."

It seemed simple because in the beginning it was simple, with the Lipan woman sitting at her husband's grave. But now there was more to it. The putting him against the wall and tying him to the cross had made it something else. Still, there was no reason to forget the Lipan woman. No matter if she didn't have a face and no matter what she looked like. And no matter if it was not happening the way it was supposed to happen. The trouble now was, Tanner could stop him before he reached the narrow place, before he reached the good position to talk and make a trade.

No, the trouble was more than that. The trouble was also the woman herself, this woman sitting without speaking anymore, the person he would have to trade. He said in his mind, St. Francis, you were a simple man. Make this goddam thing that's going on simple for me.

"You say you know where you're going," R. L. Davis said. "Tell us so we'll all know."

You don't need him, Valdez thought. He said, "If we get there, you see it. If we don't get there, it doesn't matter, does it?"

"Listen, you know how many men he's got?"

"Not so much anymore."

"He's still got enough," R. L. Davis said. "They're going to take you and string you up, if you aren't shot dead before. But either way, it's the end of old Bob Valdez."

"How's your head?"

"It still hurts."

"Close your mouth or I make it hurt worse, all right?"

"I helped you," R. L. Davis said. "You owe me something. I could have left you out there, but being a white man I went back and cut you loose."

"What do you want?" Valdez asked.

"What do you think? I cut you loose, you cut me loose and let me go."

Valdez nodded slowly. "All right. When we leave."

Davis looked at him hard. "You mean it?"

Valdez

felt the Erin woman looking at him also. "As you say, I owe it to you."

"It's not some kind of trick?"

"How could it be a trick?"

"I don't know. I just don't trust you."

Valdez shrugged. "If you're free, what difference does it make?"

"You're cooking something up," R. L. Davis said.

"No." Valdez shook his head. "I only want you to do me a favor."

"What's that?"

"Give Mr. Tanner a message from me. Tell him he has to pay the Lipan, but now I'm not sure I give him back his woman."

He felt her staring at him again, but he looked out into the darkness thinking about what he had said, realizing that it was all much simpler in his mind now.

It was two o'clock in the morning when Valdez and the Erin woman moved out leading Davis's bareback sorrel horse. They left Davis tied to his saddle with his own bandana knotted around his mouth. As Valdez tied it behind his head, Davis twisted his neck, pushing out his jaw.

"You gag me I won't be able to yell for help!"

"Very good," Valdez said.

"They might not find me!"

"What's certain in life?" Valdez asked. He got the bandana between Davis's teeth and tightened it, making the knot. "There. When it's light stand up and carry your saddle down the hill. They'll find you."

He would have liked to hit Davis once with his fist. Maybe twice. Two good ones in the mouth. But he'd let it go; he'd cut him fairly good with the Remington. Mr. R. L. Davis was lucky.

Now a little luck of your own, Valdez thought.

They walked the horses through the darkness with ridges and shadowed rock formations above them, Valdez leading the way and taking his time, moving with the clear sound of the horses on broken rock and stopping to listen in the night silence. Once, in the hours they traveled before dawn, they heard a single gunshot, a thin sound in the distance, somewhere to the east; then an answering shot far behind them. Tanner's men firing at shadows, or locating one another. But they heard no sounds close to them that could have been Tanner's riders. Maybe you're having some more luck and you'll get through, Valdez thought. Maybe St. Francis listened and he's making it easier. Hey, Valdez said. Keep Sister Moon behind the clouds so they don't see us. They moved through the night until a faint glow began to wash the sky and the ground shadows became diffused and the shapes of the rock formations and trees were more difficult to see. The moment before dawn when the Apache came through the brush with bear grass in his headband and you didn't see him until he was on you. The time when it was no longer night, but not yet morning. A time to rest, Valdez thought.

Charlie Martz and Other Stories: The Unpublished Stories

Charlie Martz and Other Stories: The Unpublished Stories Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #2

Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #2 Fire in the Hole

Fire in the Hole Tishomingo Blues (2002)

Tishomingo Blues (2002) Djibouti

Djibouti When the Women Come Out to Dance: Stories

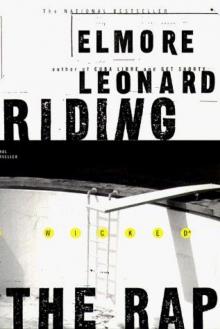

When the Women Come Out to Dance: Stories Riding the Rap

Riding the Rap Moment of Vengeance and Other Stories

Moment of Vengeance and Other Stories Raylan

Raylan Touch

Touch Mr Majestyk

Mr Majestyk Swag

Swag Road Dogs

Road Dogs La Brava

La Brava The Hot Kid

The Hot Kid Valdez Is Coming: A Novel

Valdez Is Coming: A Novel Be Cool

Be Cool The Law at Randado

The Law at Randado The Bounty Hunters

The Bounty Hunters When the Women Come Out to Dance

When the Women Come Out to Dance 310 to Yuma and Other Stories (1953)

310 to Yuma and Other Stories (1953) Tishomingo Blues

Tishomingo Blues Cat Chaser

Cat Chaser Pagan Babies

Pagan Babies Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #1

Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #1 52 Pickup

52 Pickup Stick

Stick The Moonshine War

The Moonshine War Valdez Is Coming

Valdez Is Coming City Primeval

City Primeval Rum Punch

Rum Punch Out of Sight

Out of Sight Naked Came the Manatee (1996)

Naked Came the Manatee (1996) Killshot

Killshot Cuba Libre

Cuba Libre Forty Lashes Less One

Forty Lashes Less One The Complete Western Stories of Elmore Leonard

The Complete Western Stories of Elmore Leonard Pronto

Pronto Split Images

Split Images Last Stand at Saber River

Last Stand at Saber River The Switch

The Switch Three-Ten to Yuma and Other Stories

Three-Ten to Yuma and Other Stories Bandits

Bandits Comfort to the Enemy and Other Carl Webster Stories

Comfort to the Enemy and Other Carl Webster Stories Hombre

Hombre Trail of the Apache and Other Stories

Trail of the Apache and Other Stories LaBrava

LaBrava Gold Coast

Gold Coast Jackie Brown

Jackie Brown Escape From Five Shadows

Escape From Five Shadows Karen Makes out (1996)

Karen Makes out (1996) Up in Honey's Room

Up in Honey's Room How Carlos Webster Changed His Name to Carl and Became a Famous Oklahoma Lawman (2003)

How Carlos Webster Changed His Name to Carl and Became a Famous Oklahoma Lawman (2003) Mr. Paradise

Mr. Paradise The Hunted

The Hunted Freaky Deaky

Freaky Deaky Louly and Pretty Boy (Ss)

Louly and Pretty Boy (Ss) Glitz

Glitz A Coyote's in the House

A Coyote's in the House The Big Bounce jr-1

The Big Bounce jr-1 Up in Honey's Room cw-2

Up in Honey's Room cw-2 Unknown Man #89 jr-3

Unknown Man #89 jr-3 Get Shorty: A Novel cp-1

Get Shorty: A Novel cp-1 Gunsights

Gunsights Riding the Rap rg-2

Riding the Rap rg-2