- Home

- Elmore Leonard

Three-Ten to Yuma and Other Stories Page 11

Three-Ten to Yuma and Other Stories Read online

Page 11

He felt a little better. Facing her would not be pleasant—but it still wasn’t his fault.

He rolled over, momentarily studying the ceiling, then he let his head roll on the mattress and he saw the man on the other bunk watching him. He was sitting hunched over, making a cigarette.

Pete Given closed his eyes and he could still see the man. He didn’t seem big, but he had a stringy hard-boned look. Sharp cheekbones and dull-black hair that was cut short and brushed forward to his forehead. No mustache, but he needed a shave and it gave the appearance of an almost full-grown mustache.

He opened his eyes again. The man was drawing on the cigarette, still watching him.

“What time you think it is?” Given asked.

“About nine.” The man’s voice was clear though he barely moved his mouth.

Given said, “If you were one of them over to the Continental I’d just as soon shake hands this morning.”

The man did not reply.

“You weren’t there, then?”

“No,” he said now.

“What’ve they got you for?”

“They say I shot a man.”

“Oh.”

“Fact is, they say I shot two men, during the Grant stage holdup.”

“Oh.”

“When the judge comes tomorrow, he’ll set a court date. Give the witnesses time to get here.” He stood up, saying this. He was tall, above average, but not heavy.

“Are you”—Given hesitated—“Obie Ward?”

The man nodded, drawing on the cigarette.

“Somebody last night said you were here. I’d forgot about it.” Given spoke louder, trying to make his voice sound natural, and now he raised himself on an elbow.

Obie Ward asked, “Were you drinking last night?”

“Some.”

“And got in a fight.”

Given sat up, swinging his legs off the bunk and resting his elbows on his knees. “One of my partners got in trouble and we had to help him.”

“You don’t look so good,” Ward said.

“I feel okay.”

“No,” Ward said. “You don’t look so good.”

“Well, maybe I just look worse’n I am.”

“How’s your stomach?”

“It’s all right.”

“You look sick to me.”

“I could eat. Outside of that I got no complaint.” Given stood up. He put his hands on the small of his back and stretched, feeling the stiffness in his body. Then he raised his arms straight up, stretching again, and yawned. That felt good. He saw Obie Ward coming toward him, and he lowered his arms.

Ward reached out, extending one finger, and poked it at Pete Given’s stomach. “How’s it feel right there?”

“Honest to gosh, it feels okay.” He smiled looking at Ward, to show that he was willing to go along with a joke, but he felt suddenly uneasy. Ward was standing too close to him and Given was thinking: What’s the matter with him?—and the same moment he saw the beard-stubbled face tighten.

Ward went back a half step and came forward, driving his left fist into Given’s stomach. The boy started to fold, a gasp coming from his open mouth, and Ward followed with his right hand, bringing it up solidly against the boy’s jaw, sending him back, arms flung wide, over the bunk and hard against the wall. Given slumped on the mattress and did not move. For a moment Ward looked at him, then picked up his cigarette from the floor and went back to his bunk.

He was sitting on the edge of it when Given opened his eyes—smoking another cigarette, drawing on it and blowing the smoke out slowly.

“Are you sick now?”

Given moved his head, trying to lift it, and it was an effort to do this. “I think I am.”

Ward started to rise. “Let’s make sure.”

“I’m sure.”

WARD RELAXED AGAIN. “I told you so, but you didn’t believe me. I been watching you all morning and the more I watched, the more I thought to myself: Now there’s a sick boy. Maybe you ought to even have a doctor.”

Given said nothing. He stiffened as Ward rose and came toward him.

“What’s the matter? I’m just going to see you’re more comfortable.” Ward leaned over, lifting the boy’s legs one at a time, and pulled his boots off, then pushed him, gently, flat on the bunk and covered him with a blanket that was folded at the foot of it. Given looked up, holding his body rigid, and saw Ward shake his head. “You’re a mighty sick boy. We got to do something about that.”

Ward crossed the cell to his bunk, and standing at one end, he lifted it a foot off the floor and let it drop. He did this three times, then went down to his hands and knees and, close to the floor, called, “Hey, Marshal!” He waited. “Marshal, we got a sick boy up here!” He rose, winking at Given, and sat down on his bunk.

Minutes later a door at the back end of the hallway opened and Boynton came toward the cell. A deputy with a shotgun, his day man, followed him.

“What’s the matter?”

Ward nodded. “The boy’s sick.”

“He ought to be,” Boynton said.

Ward shrugged. “Don’t matter to me, but I got to listen to him moaning.”

Boynton looked toward Given’s bunk. “A man that don’t know how to drink has got to expect that.” He turned abruptly. Their steps moved down the hall and the door slammed closed.

“No sympathy,” Ward said. He made another cigarette, and when he had lit it he walked over to Given’s bunk. “He’ll come back in about two hours with our dinner. You’ll still be in bed, and this time you’ll be moaning like you got belly cramps. You got that?”

Staring up at him, Given nodded his head stiffly.

At a quarter to twelve Boynton came up again. This time he ordered Ward to lie down flat on his bunk. He unlocked the door then and remained in the hall as the day man came in with the dinner tray and placed it in the middle of the floor.

“He still sick?” Boynton stood in the doorway holding a sawed-off shotgun.

Ward turned his head on the mattress. “Can’t you hear him?”

“He’ll get over it.”

“I think it’s something else,” Ward said. “I never saw whiskey hold on like that.”

“You a doctor?”

“As much a one as you are.”

Boynton looked toward the boy again. Given’s eyes were closed and he was moaning faintly. “Tell him to eat something,” Boynton said. “Maybe then he’ll feel better.”

“I’ll do that,” Ward said. He was smiling as Boynton and his deputy moved off down the hall.

Lying on his back, his head turned on the mattress, Given watched Ward take a plate from the tray. It looked like stew.

“Can I have some?” Given said.

Chewing, Ward shook his head.

“Why not?”

Ward swallowed. “You’re too sick.”

“Can I ask you a question?”

“Go ahead.”

“How come I’m sick?”

“You haven’t figured it?”

“No.”

“I’ll give you a hint. We’ll get our supper about six. Watch the two that bring it up.”

“I don’t see what they’d have to do with me.”

“You don’t have to see.”

Given was silent for some time. He said then, “It’s got to do with you busting out.”

Obie Ward grinned. “You got a head on your shoulders.”

Boynton came up a half hour later. He stood in the hall and when his deputy brought out the tray, his eyes went from it to Pete Given’s bunk. “The boy didn’t eat a bite,” Boynton observed.

Ward raised up on his elbow. “Said he couldn’t stand the smell of it.” He watched Boynton look toward the boy, then sank down on the bunk again as Boynton walked away. When the door down the hall closed, Ward said, “Now he believes it.”

It was quiet in the cell after that. Ward rolled over to face the wall and Pete Given, lying on his back, remained motionless, t

hough his eyes were open and he was studying the ceiling.

He tried to understand Obie Ward’s plan. He tried to see how his being sick could have anything to do with Ward’s breaking out. And he thought: He means what he says, doesn’t he? You can be sure of that much. He’s going to bust out and you got a part in it and there ain’t a damn thing you can do about it. It’s that simple, isn’t it?

OBIE WARD WAS RIGHT. At what seemed close to six o’clock they heard the door open at the end of the hall and a moment later Stan Cass and Hanley Miller were standing in front of the cell. Hanley opened the door and stood holding a sawed-off shotgun as Cass came in with the tray.

Cass half turned to face Ward sitting on his bunk, then went down to one knee, lowering the tray to the floor, and he did not take his eyes from Ward. He rose then and turned as he heard groans from the other bunk.

“What’s his trouble?”

Ward looked up. “Didn’t your boss tell you?”

“He told me,” Cass said, “but I believe what I see.”

“Help yourself, then.”

Cass turned sharply. “You shut your mouth till I want to hear from you!”

“Yes, sir,” Ward said. His dark face was expressionless.

Cass stared at him, his thumbs hooked in his gun belt. “You think you’re somethin’, don’t you?”

Ward’s head moved from side to side. “Not me.”

“I’d like to see you pull somethin’,” Cass said. His right hand opened and closed, moving closer to his hip. “I’d just like to see you get off that bunk and pull somethin’.”

Ward shook his head. “Somebody’s been telling you stories.”

“I think they have,” Cass said. He hesitated, then walked out, slamming the door shut.

Ward called to him through the bars, “What about the boy?”

“You take care of him,” Cass said, moving off. Hanley Miller followed, looking back over his shoulder.

Ward waited until the back door closed, then picked up a plate and began to eat and not until he was almost finished did he notice Given watching him.

“Did you see anything?”

Given came up on his elbow slowly. He looked at the tray on the floor, then at Ward. “Like what?”

“Like the way that deputy acted.”

“He wanted you to try something.”

“What else?”

Given pictured Cass again in his mind. “He was wearing a gun.” Suddenly he seemed to understand and he said, “The marshal wasn’t wearing any, but this one was!”

Ward grinned. “And he knows you’re sick. First his boss told him, then he saw it with his own eyes.” Ward put down the plate and he made a cigarette as he walked over to Given’s bunk. “I’ll tell you something else,” he said, standing close to the bunk. “I’ve been here seven days. For seven days I watch. I see the marshal. He knows what he’s doing and he don’t wear a gun when he comes in here. A man out in the hall with a scattergun’s enough. Then this other one they call Cass. He walks like he can feel his gun on his hip. He’s not used to it, but it feels good and he’d like an excuse to use it. He even wears it in here, though likely he’s been told not to. What does that tell you? He’s sure of himself, but he’s not smart. He wants to see me try something—and he’s sure he can get his gun out if I do. For seven days I see this and there’s nothing I can do about it—until this morning.”

Given nodded thoughtfully, but said nothing.

“This morning I saw you,” Ward went on, “and you looked sick. There it was.”

Given nodded again. “I guess I see.”

“We let the marshal know about it. He tells Cass when he comes on duty. Cass comes up and sure enough, you’re sick.”

“Yeah?”

“Then Cass comes up the next time—understand it’ll be dark outside by then: he brings supper up at six, but he must go out to eat after that because he doesn’t come back for the tray till almost eight—and he’s not surprised to see you even sicker.”

“How does he see that?”

“You scream like your stomach’s been pulled out and you roll off the bunk.”

“Then what?”

“Then you don’t have to do anything else.”

Given’s eyes held on Ward’s face. He swallowed and said, as evenly as he could, “Why should I help you escape?” He saw it coming and he tried to roll away, but it was too late and Ward’s fist came down against his face like a mallet.

He was dazed and there was a stinging throbbing over the entire side of his face, but he was conscious of Ward leaning close to him and he heard the words clearly. “I’ll kill you. That reason enough?”

After that he was not conscious of time. His eyes were closed and for a while he dozed off. Then, when he opened his eyes, momentarily he could remember nothing and he was not even sure where he was, because he was thinking of nothing, only looking at the chipped and peeling adobe wall and feeling a strange numbness over the side of his face.

His hand was close to his face and his fingers moved to touch his cheekbone. The skin felt swollen hard and tight over the bone, and just touching it was painful. He thought then: Are you afraid for your own neck? Of course I am!

But it was more than fear that was making his heart beat faster. There was an anger inside of him. Anger adding excitement to the fear and he realized this, though not coolly, for he was thinking of Ward and Mary Ellen and himself as they came into his mind, not as he called them there.

Ward had said, Roll off the cot.

All right.

He heard the back door open and instantly Ward muttered, “You awake?” He turned his head to see Ward sitting on the edge of the bunk, his hands at his sides gripping the mattress. He heard the footsteps coming up the hall.

“I’m awake.”

“Soon as he opens the door,” Ward said, and his shoulders seemed to relax.

As soon as he opens the door.

He heard Cass saying something and a key rattled in the lock. The squeak of the door hinges—

He groaned, bringing his knees up. His heart was pounding and a heat was over his face and he kept his eyes squeezed closed. He groaned again, louder this time, and doing it he rolled to his side, hesitated at the edge of the mattress, then let himself fall heavily to the floor.

“What’s the matter with him!”

Four steps on the plank floor vibrated in his ear. A hand took his shoulder and rolled him over. Opening his eyes, he saw Cass leaning over him.

Suddenly then, Cass started to rise, his eyes stretched open wide, and he twisted his body to turn. An arm came from behind hooking his throat, dragging him back, and a hand was jerking the revolver from its holster.

HANLEY MILLER tried to push away from the bars to bring up the shotgun. It clattered against the bars and on top of the sound came the deafening report of the revolver. Hanley doubled up and went to the floor, clutching his thigh.

Cass’s mouth was open and he was trying to scream as the revolver flashed over his head and came down. The next moment Ward was throwing Cass’s limp weight aside. Ward stumbled, clattering over the tray in the middle of the floor, almost tripping.

Given saw Ward go through the wide-open door. He glanced then at Hanley Miller lying on the floor. Then, looking at Ward’s back, the thought stabbed suddenly, unexpectedly, in his mind—

Get him!

He hesitated, though the hesitation was in his mind and it was part of a moment. Then he was on his feet, moving quickly, silently, in his stocking feet, stooping to pick up the sawed-off shotgun, turning and seeing Ward near the door. Now Given was running down the hallway, now swinging open the door that had just closed behind Ward.

Ward was on the back-porch landing, starting down the stairs, and he wheeled, bringing up the revolver as the door opened, as he saw Pete Given on the landing, as he saw the stubby shotgun barrels swinging savagely in the dimness.

Ward fired hurriedly, wildly, the same moment the double barrels s

lashed against the side of his head. He screamed as he lost his balance and went down the stairway. At the bottom he tried to rise, groping momentarily, feverishly, for his gun. As he came to his feet, Pete Given was there—and again the shotgun cut viciously against his head. Ward went down, falling forward, and this time he did not move.

Given sat down on the bottom step, letting the shotgun slip from his fingers. A lantern was coming down the alley.

Boynton appeared in the circle of lantern light. He looked from Obie Ward to the boy, not speaking, but his eyes remained on Given until he stepped past him and went up the stairs.

A man stooped next to him, extending an already rolled cigarette. “You look like you want a smoke.”

Given shook his head. “I’d swallow it.”

The man nodded toward Obie Ward. “You took him by yourself?”

“Yes, sir.”

“That must’ve been something to see.”

“I don’t know—it happened so fast.” In the crowd he heard Obie Ward’s name over and over—someone asking if he was dead, a man bending over him saying no…someone asking, “Who’s that boy?” and someone answering, “I don’t know, but he’s got enough guts for everybody.”

Boynton appeared on the landing and called for someone to get the doctor. He came down and Given stood up to let him pass. The man who was holding the cigarette said, “John, this boy got Obie all by himself.”

Boynton was looking at Ward. “I see that.”

“More’n I would’ve done,” the man said, shaking his head.

“More’n most anybody would’ve done,” Boynton answered. He looked at Given then, studying him openly. He said then, “I’ll recommend to the judge we drop the charges against you.”

Given nodded. “That’d be fine.”

“Anxious to get home to your wife?”

“Yes, sir.”

For a moment Boynton was silent. His expression was mild, but his eyes were fastened on Pete Given’s face as if he were trying to read something there, some mark of character that would tell him about this boy.

“On second thought,” Boynton said abruptly, “I’ll tear your name right out of the record book, if you’ll take a deputy job. You won’t even have to put a foot in court.”

Charlie Martz and Other Stories: The Unpublished Stories

Charlie Martz and Other Stories: The Unpublished Stories Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #2

Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #2 Fire in the Hole

Fire in the Hole Tishomingo Blues (2002)

Tishomingo Blues (2002) Djibouti

Djibouti When the Women Come Out to Dance: Stories

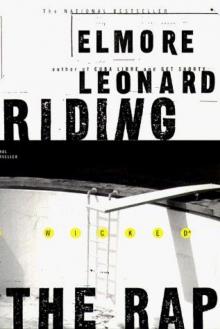

When the Women Come Out to Dance: Stories Riding the Rap

Riding the Rap Moment of Vengeance and Other Stories

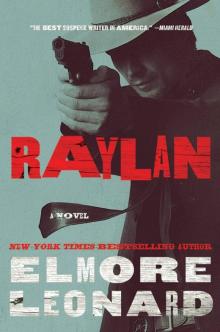

Moment of Vengeance and Other Stories Raylan

Raylan Touch

Touch Mr Majestyk

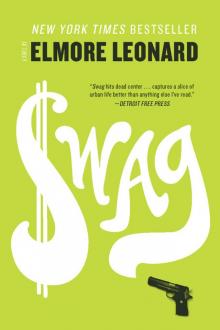

Mr Majestyk Swag

Swag Road Dogs

Road Dogs La Brava

La Brava The Hot Kid

The Hot Kid Valdez Is Coming: A Novel

Valdez Is Coming: A Novel Be Cool

Be Cool The Law at Randado

The Law at Randado The Bounty Hunters

The Bounty Hunters When the Women Come Out to Dance

When the Women Come Out to Dance 310 to Yuma and Other Stories (1953)

310 to Yuma and Other Stories (1953) Tishomingo Blues

Tishomingo Blues Cat Chaser

Cat Chaser Pagan Babies

Pagan Babies Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #1

Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #1 52 Pickup

52 Pickup Stick

Stick The Moonshine War

The Moonshine War Valdez Is Coming

Valdez Is Coming City Primeval

City Primeval Rum Punch

Rum Punch Out of Sight

Out of Sight Naked Came the Manatee (1996)

Naked Came the Manatee (1996) Killshot

Killshot Cuba Libre

Cuba Libre Forty Lashes Less One

Forty Lashes Less One The Complete Western Stories of Elmore Leonard

The Complete Western Stories of Elmore Leonard Pronto

Pronto Split Images

Split Images Last Stand at Saber River

Last Stand at Saber River The Switch

The Switch Three-Ten to Yuma and Other Stories

Three-Ten to Yuma and Other Stories Bandits

Bandits Comfort to the Enemy and Other Carl Webster Stories

Comfort to the Enemy and Other Carl Webster Stories Hombre

Hombre Trail of the Apache and Other Stories

Trail of the Apache and Other Stories LaBrava

LaBrava Gold Coast

Gold Coast Jackie Brown

Jackie Brown Escape From Five Shadows

Escape From Five Shadows Karen Makes out (1996)

Karen Makes out (1996) Up in Honey's Room

Up in Honey's Room How Carlos Webster Changed His Name to Carl and Became a Famous Oklahoma Lawman (2003)

How Carlos Webster Changed His Name to Carl and Became a Famous Oklahoma Lawman (2003) Mr. Paradise

Mr. Paradise The Hunted

The Hunted Freaky Deaky

Freaky Deaky Louly and Pretty Boy (Ss)

Louly and Pretty Boy (Ss) Glitz

Glitz A Coyote's in the House

A Coyote's in the House The Big Bounce jr-1

The Big Bounce jr-1 Up in Honey's Room cw-2

Up in Honey's Room cw-2 Unknown Man #89 jr-3

Unknown Man #89 jr-3 Get Shorty: A Novel cp-1

Get Shorty: A Novel cp-1 Gunsights

Gunsights Riding the Rap rg-2

Riding the Rap rg-2