- Home

- Elmore Leonard

Unknown Man #89 jr-3 Page 11

Unknown Man #89 jr-3 Read online

Page 11

Then, this morning, a couple of vodkas and orange juice. At lunch in Drayton Plains he’d decided to pass on the Bloody Marys and had two beers with his chili. Then another bowl, it was so good, and another couple of beers. Then, two bars before this one, four bourbons. Two, three more here with the friendly bartender. That was thirteen drinks and it was only a quarter to five.

His wife or somebody had told him once, his problem was he didn’t count his drinks. Okay, he was counting them. He could continue to drink socially till midnight and bring the total to thirty without any trouble. A good two whole fifths’ worth of booze. But why stop at midnight? He wouldn’t; he’d keep going.

He didn’t have to, though. Right now he was at the border. With a relatively clear head he could say, “Good-bye brains,” and start pouring them down. Or he could quit right now. Except it would seem like stopping right in the middle, before he’d taken advantage of getting drunk, before he’d had any fun. Maybe a couple more days. Relax and let it happen. Look into some of the interesting afternoon lady drinkers he’d seen, the housewives with their gimlets and stingers and Black Russians. Tell them about serving the papers to the rock group and how he’d got his picture in the Free Press. Tell that one a few more times. Show the housewives what a funny guy he was. Score in a motel on Telegraph with a fifth of vodka, pop out of the machine. Or cold duck, because the housewife thought cold duck was romantic.

By tomorrow afternoon he wouldn’t be thinking about it, he’d be doing it. Half in the bag trying to do it, sweating, and nothing happening. Or quit right now. Four years ago he was ready to quit on September 28, but he had put it off a few days because October 1 would be easier to remember as the day he quit and joined AA. He had quit six or seven times since then and wasn’t sure of the last date. It didn’t matter. He had been clean three and a half years and now, for some reason, he was sitting in a bar drinking. Deciding if he should keep going. Actually considering it, knowing the pain he would experience when he finally stopped cold and withdrew. It wasn’t a hangover pain; that was simple, you could numb it with aspirin. The pain in withdrawal was the extreme feeling of anxiety that Ryan remembered well-a raw, hypersensitive feeling, like a sunburned nervous system-wanting to either take a drink or go out the window. With Ryan it would last a couple of days while he paced and filled himself with liquids and ate B-12 tablets like peanuts.

The question, was it worth it? Of course not? But that didn’t seem to matter, because it didn’t have anything to do with now.

Why he was drinking didn’t matter either. Because he was Irish or basically insecure? He was drinking. He could admit he was powerless over it once he got going, and he was still drinking. Sitting quietly in a bar, looking at his options and his reflection. He looked good, tan in the tinted bar mirror. His memory wasn’t too sharp, though. He wasn’t sure of the exact date, April 25 or 26. May 1 was a little too far off. The thing to do was call one of his friends in AA, admit he was fucking up and needed help, a kick in the ass. Or he could go to a meeting tonight. He hadn’t been to a meeting in about four months, and maybe that was his problem. Find one in the area. Call the main office and find out where to go in Pontiac. Go home and take a shower and a quick nap first, have something to eat. Pay and get out of here.

Or have just one more.

14

“I WOKE UP last night and looked at the ceiling,” the woman across from Ryan said. “And you know what? It wasn’t spinning around. I got up to go to the bathroom and I found it without bumping into furniture or knocking anything over. It was right where it was supposed to be. Sometimes I used to wake up in the morning on the floor and I’d say a prayer, before opening my eyes, that I’d know where I was.”

The table leader said, “I know what you mean. The first six months to a year in the program, I’d still wake up in the morning expecting to be hung over. I was amazed I actually felt normal.”

The meeting was in a windowless basement room of Saint Joseph Mercy Hospital, Pontiac. Cinder-block wall, fluorescent lights, lunchroom tables and folding chairs, the coffeemaker, the Styrofoam cups, the cookies. It could be an AA meeting anywhere, with groups of eight to twelve people at the five tables.

Another of the women was saying that sometimes she’d wake up in a motel room and there’d be a man with her she’d never seen before in her life and she’d scream at him, “What’re you doing here! Get out!” The poor guy would be baffled-after the beautiful evening they’d had that she didn’t remember.

There were four women and seven men at the table, including Ryan. He wasn’t sure if he was going to say anything when the table leader got to him. He might pass, say he just wanted to listen this evening. He wondered if there might be a trace of whiskey on his breath. He asked himself then, Would it matter? Like someone might point to him and they’d throw him out of the program. Amazing, two days of drinking and the guilt feelings were back. He had stayed away from meetings too long. He knew it, but he didn’t feel part of it tonight. At least not yet.

A man two chairs away from him said, “Thank you. I’m Paul, I’m an alcoholic, and I’m very glad to be here. You know, there’s a big difference between admitting you’re an alcoholic and accepting the fact. That’s why I like to sit at a First Step table every so often. Not only to listen, but to keep reminding myself that I’m powerless over alcohol. I wasn’t like Ed there, who mentioned binge drinking, go off for a couple of weeks and then straighten out, stay sober awhile. Shit, I was drunk all the time.”

What were you? Ryan was thinking, a moderate drunk? A neat drunk. He had always hung up his clothes at night and only wet his pants once.

A woman about forty-five said that Saturday night finally did it when she came home drunk and had a fight with her fourteen-year-old daughter: the unbelievable language she used, screaming at the child, Mommy in one of her finest scenes. The next morning she wanted to die. But she called a friend in the program and went to a meeting that night. She had come to meetings Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, and she was here tonight and was going to keep coming.

The guy next to Ryan leaned close to him, reaching for the ashtray, and said, “What does she want, a fucking medal? She doesn’t have any choice.”

When the guy’s turn came to speak to the table, he said, “I wasn’t an alcoholic, like the rest of you drunks. Hell no. In a two-year period I got fired from three jobs, my wife divorced me, I was arrested twice for drunk driving, I smashed up the garage and five cars, but I wasn’t an alcoholic. I was a heavy social drinker.” There was laughter and some nodding heads. Ryan smiled.

Everyone at the table had been there.

“Cats slept in my car,” a woman said. “It had so many holes in it from smashups.”

Ryan remembered scraping the side of his sister’s house pulling into the drive, ruining the flower bed. He remembered picking up the strip of molding and throwing it in the car while his brother-in-law ran his hand gently over the brick wall, like the scrape mark was a wound.

“I wouldn’t, the way I was, I wouldn’t go anywhere unless I was sure I could get a drink,” the woman was saying now. “I’d be at a school PTA meeting, I’d say excuse me, like I was going to the bathroom. I’d go out to my car. I always kept a couple of six-packs in the trunk.”

In a cooler, Ryan remembered. Unless it was winter. Open the trunk like it was a refrigerator. Drive with the can between your legs. He looked at his watch.

Nine o’clock. Another half hour. The room was close and he could feel himself perspiring. All the hot coffee and cigarettes. The ashtrays around the table were full. Walk into a room like this anywhere, and if everybody was drinking coffee and smoking cigarettes it was an AA meeting.

A man was saying that two years ago, when he and his wife were in Europe, they’d taken a boat trip down the Rhine. He didn’t see much, though. The only thing he looked for along the river was liquor stores.

The table leader said to Ryan, “I’m sorry, I don’t know your name. Would you like to

say a few words?”

Ryan had lighted a cigarette, getting ready, knowing his turn was coming. He said, “Thank you.” He paused. The people at the table waited.

“I was going to pass,” Ryan said then, “or make something up… but I might as well tell you where I am. I’ve been in the program three and a half years.” He paused. “I’m Jack, and I’m an alcoholic. I got drunk yesterday and the day before, and I thought I’d probably keep going a few more days. Why I started drinking again, I don’t know. Maybe because my car needs new shock absorbers. Or it was King Farouk’s birthday. The reason doesn’t matter, does it? I slipped-no, I didn’t slip, I intentionally got drunk-because I’ve stayed away from meetings too long, four months, and I started relying on myself instead of the program. I forgot, I guess, that when you give up one way of life, drinking, you have to substitute something else for it. Otherwise all you’ve done, you’ve quit drinking, but you’ve still got the same old resentments and hang-ups inside. You’re sober but you’re miserable, hard to get along with. You’re what’s called a dry drunk. Sober, but that’s all. Well, I’ve been very happy the last couple of years. Not only because I’ve been sober and feel better physically, but because the program has changed my attitude.” He paused. “A friend of mine has a sign on the wall at his office, it says No More Bullshit. And that’s the way I feel, or want to get back to feeling again. I know I can be myself. I don’t have to play a role, put up a front, pretend to be something I’m not. I even listen to what people say now. I can argue without getting mad. If the other person gets mad, that’s his problem. I don’t feel the need to convince everybody I’m right. Somebody said here tonight, ‘I like myself now, and it’s good to be able to say that.’ I had fun drinking, I’ll admit it. At least, I had fun for about ten or twelve years and, fortunately, I didn’t get in too much trouble or hit bottom and sleep in the weeds. But once I realized I was thinking about the next drink while I still had one in front of me-once I started making up excuses to drink and got drunk every time I went out-I was in more trouble than I realized. You know what happens after that, drinking not to feel good but just to feel normal, to get your nerves under control. What I’m saying, I’d be awfully dumb to go back to that when I can feel good and be myself-that’s the important thing-without drinking. I don’t know where we got the idea we need to drink to bring ourselves out.”

Ryan paused again, not sure where he was going.

“I’m glad I’m here and can tell you what I feel,” he said then, “instead of sitting in a bar thinking. The best thing we can do, besides staying out of bars, is try to stay out of our heads.”

It was a good feeling, coming out instead of beating himself down. He picked up his empty coffee cup, and the guy’s cup next to him, and went over to the urn and filled them up. When he sat down again, a girl at the end of the table was speaking.

She was saying she thought the sign was a great idea. No More Bullshit. Because that’s what the program, to her, seemed to be all about. The idea, quit pretending and be yourself… a way to self-awareness that everybody, not just alcoholics, seems to be more interested in today. That’s what had surprised her most about the program, the positive aspect of it. Not simply abstaining from alcohol, but as Jack said, substituting something positive for it, a totally different way of life, not inner-directed anymore, but outgoing.

The girl stopped.

Ryan was sipping his coffee.

“I’m sorry,” she said then. “I started talking-I forgot to say I’m Denise, and I’m an alcoholic.”

Ryan lit another cigarette and leaned forward with his elbows on the table, watching her. It couldn’t be the same girl. But now the voice was familiar.

“I have the feeling everything I say you’ve heard before,” Denise said, “but I guess that’s part of it too. We can empathize, put ourselves in each other’s places.”

The nose was the same. Her face was different, it seemed narrower, smaller. Her blond hair was much shorter. It fell in a nice curve close to one eye, and she’d brush it away with the tips of her fingers.

“I reached the point finally, I guess I did think about killing myself, but even then I put off thinking how I would do it, whether to go off the bridge or turn the gas on or what. I’d think about it tomorrow, after I finished the half gallon of wine.”

The empty Gallo bottles on the kitchen floor. The girl lying on the daybed with her hair in her face. Hair and lint on the dark turtleneck. Ryan remembered it. The greasy blue jeans and pale white unprotected feet. Moving her foot and not knowing someone was there watching it move. The girl at the table would be about the same age, twenty-eight. She wore a navy-blue sweater with the collar of a print blouse showing. She looked fresh, clean.

“It was a feeling that I wanted to get out of myself. Do you know what I mean? Every once in a while I’d see myself, what I’d become, and I’d say, ‘What am I doing here? This isn’t me.’ I couldn’t stop thinking. Do you know what I mean? Going around in circles, afraid of not particular things but everything.”

The voice on the phone had said to him, “I don’t want to be here. I don’t want to be inside me, but I can’t get out.”

“I had some help. Right at the end, when I didn’t know what to do. I remember someone tried to help me.”

She was looking this way, but her gaze might be directed past him, or at the table leader a couple of chairs over. Ryan wasn’t sure.

“But I guess my pride screwed things up. I had to do it myself, so I ran away. Which is a pretty good trick, running away from yourself. Then I got the idea I was going to go home, the little girl wanting her mommy. But I didn’t do that either, thank God, which was probably a good thing. If I’d gotten the lectures and all the shoulds and shouldn’ts, and Mother taking my screwing-up as a personal affront, trying to hurt her-I didn’t need somebody like that, who wouldn’t even begin to understand the problem. My mother’s idea of drinking-well, never mind.”

Good, Ryan thought. It would’ve been a bad move.

“Somehow I got to a meeting. It was at Holy Trinity in Detroit, you know, in Corktown, and there was a real mixture of people there. I remember a black woman who kept referring to her higher power as God Honey. That was my first meeting. I’d find a meeting every night somewhere, and finally I came out here.” Denise paused. “I got a job, I start Monday. I’m living in Rochester in a very nice place and-the amazing thing, it seems like such a long time ago, and yet it’s only been three or four weeks. I’m still a little fuzzy about periods of time.”

Three and a half weeks, Ryan thought. Twenty-five days.

“I just hope it lasts, the good feeling.” She paused again and looked at the table leader. “Thank you.”

After the meeting they stood in lingering groups talking. Most of them seemed to know one another. Ryan got a half cup of coffee and waited. She was standing with the man from their table named Paul and the woman who used to wake up in motel rooms. Paul finally left them. They glanced over this way, then came toward him, both of them smiling. She was a good-looking girl, neat and trim, Ryan’s idea of the perfect size. The other one, he couldn’t imagine her waking up in a motel room with anyone.

“It’s Jack, isn’t it?”

“Right. Denise and…”

“This is Irene. I was just telling her-you said this was your first time, but I know I’ve seen you somewhere. Do you ever go to the Teamsters’ Hall on Sunday?”

“No, I’ve heard about it, but I’ve never been there.”

“It’s a good meeting. Eleven o’clock Sunday morning.”

“I’ll have to go sometime. Yeah, I’ve been in the program three and a half years, but this is my first time here. Usually I used to go to Beaumont.”

He was letting it get away. He wanted to ask her a question to be absolutely sure, but Irene stood there smiling at him. It had to be the same girl, now with trusting eyes, a pleasant expression, looking at him and sensing something but not remembering. He wouldn’t

have recognized her on the street.

“It was a good meeting, wasn’t it?” She seemed eager to keep going.

“Yeah, I enjoyed it. I guess I always do. Everybody’s straight, it’s the one place people tell you honestly what they think.”

“No More Bullshit,” Denise said. “I love that. I think I’ll paint it on my wall.”

“The guy I mentioned has it,” Ryan said, “is with an advertising agency. I don’t know if it helps him or not. Maybe.”

Denise smiled again. “Are you in that business?”

“No, I’m a process server.”

She nodded and seemed to be thinking about something.

“You know what that is?”

“I’ve been served, evicted, and repossessed. I know exactly what it is. Not lately, though.”

“Not in the past three or four weeks anyway, huh?”

It went past her or she didn’t hear him. She was looking at the people beginning to leave.

“I told Paul and some of the others I’d meet them for a bite,” Denise said. “Would you like to join us?”

“Fine. I’ve got a car.”

“I came with Irene. Why don’t you follow us over, unless you know where it is.”

“Where are we going?”

“I’m sorry, I thought all AAs went to Uncle Ben’s after meetings. It’s the pancake house on Huron.”

“Maybe he sick,” Tunafish said.

“Got sick all of a sudden,” Virgil said. “Park his car and walk in the hospital, say he’s sick.”

“Then he visiting somebody.”

“That’s where we’re at,” Virgil said. “Who? Bobby’s woman? Maybe so. She was in bad shape.”

“Ask him,” Tunafish said. “You know the man.”

“The man ain’t talking much. He don’t call me back. But all of a sudden he got this interest in Pontiac, going to the bars, going home, come back out here. He know something he ain’t telling.”

Charlie Martz and Other Stories: The Unpublished Stories

Charlie Martz and Other Stories: The Unpublished Stories Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #2

Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #2 Fire in the Hole

Fire in the Hole Tishomingo Blues (2002)

Tishomingo Blues (2002) Djibouti

Djibouti When the Women Come Out to Dance: Stories

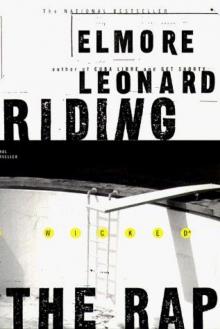

When the Women Come Out to Dance: Stories Riding the Rap

Riding the Rap Moment of Vengeance and Other Stories

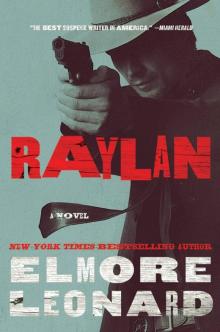

Moment of Vengeance and Other Stories Raylan

Raylan Touch

Touch Mr Majestyk

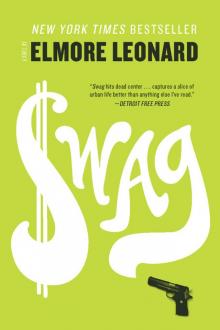

Mr Majestyk Swag

Swag Road Dogs

Road Dogs La Brava

La Brava The Hot Kid

The Hot Kid Valdez Is Coming: A Novel

Valdez Is Coming: A Novel Be Cool

Be Cool The Law at Randado

The Law at Randado The Bounty Hunters

The Bounty Hunters When the Women Come Out to Dance

When the Women Come Out to Dance 310 to Yuma and Other Stories (1953)

310 to Yuma and Other Stories (1953) Tishomingo Blues

Tishomingo Blues Cat Chaser

Cat Chaser Pagan Babies

Pagan Babies Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #1

Elmore Leonard's Western Roundup #1 52 Pickup

52 Pickup Stick

Stick The Moonshine War

The Moonshine War Valdez Is Coming

Valdez Is Coming City Primeval

City Primeval Rum Punch

Rum Punch Out of Sight

Out of Sight Naked Came the Manatee (1996)

Naked Came the Manatee (1996) Killshot

Killshot Cuba Libre

Cuba Libre Forty Lashes Less One

Forty Lashes Less One The Complete Western Stories of Elmore Leonard

The Complete Western Stories of Elmore Leonard Pronto

Pronto Split Images

Split Images Last Stand at Saber River

Last Stand at Saber River The Switch

The Switch Three-Ten to Yuma and Other Stories

Three-Ten to Yuma and Other Stories Bandits

Bandits Comfort to the Enemy and Other Carl Webster Stories

Comfort to the Enemy and Other Carl Webster Stories Hombre

Hombre Trail of the Apache and Other Stories

Trail of the Apache and Other Stories LaBrava

LaBrava Gold Coast

Gold Coast Jackie Brown

Jackie Brown Escape From Five Shadows

Escape From Five Shadows Karen Makes out (1996)

Karen Makes out (1996) Up in Honey's Room

Up in Honey's Room How Carlos Webster Changed His Name to Carl and Became a Famous Oklahoma Lawman (2003)

How Carlos Webster Changed His Name to Carl and Became a Famous Oklahoma Lawman (2003) Mr. Paradise

Mr. Paradise The Hunted

The Hunted Freaky Deaky

Freaky Deaky Louly and Pretty Boy (Ss)

Louly and Pretty Boy (Ss) Glitz

Glitz A Coyote's in the House

A Coyote's in the House The Big Bounce jr-1

The Big Bounce jr-1 Up in Honey's Room cw-2

Up in Honey's Room cw-2 Unknown Man #89 jr-3

Unknown Man #89 jr-3 Get Shorty: A Novel cp-1

Get Shorty: A Novel cp-1 Gunsights

Gunsights Riding the Rap rg-2

Riding the Rap rg-2